Smallpox was one of the most feared infections of the past because not only did it kill many people who contracted it but those who survived were badly disfigured from the scarring left on the skin, particularly on the face.

Variolation

Very little could be done to prevent smallpox in Britain until 1713 when the practice of inoculation (also known as variolation) was introduced into the country by Emanuel Timoni who wrote to the Royal Society about how he had seen the technique performed on a visit to Turkey. It involved pricking material from the pocks of a smallpox sufferer into the skin of a person requiring immunisation, and thus rendering them immune to further infection.

Nobody took much notice of his communication but eight years later Lady Mary Wortley Montague, who had also been travelling in Turkey, popularised the technique in London. Although the medical profession was at first very sceptical of the procedure, a number of people, mostly apothecaries and surgeons, became well known “inoculators”. Their reputation rested on their ability to induce a very mild form of smallpox after inoculating their patient.

News of the technique rapidly spread to other parts of the country including Plymouth where Dr William Oliver was working as a physician before moving to Bath. Oliver was keen to promote the technique but as a physician he was reluctant to perform the procedure, leaving the actual inoculation to a surgeon with whom he worked.

Inoculation was the only way to immunise a person against smallpox until the latter part of the eighteenth century.

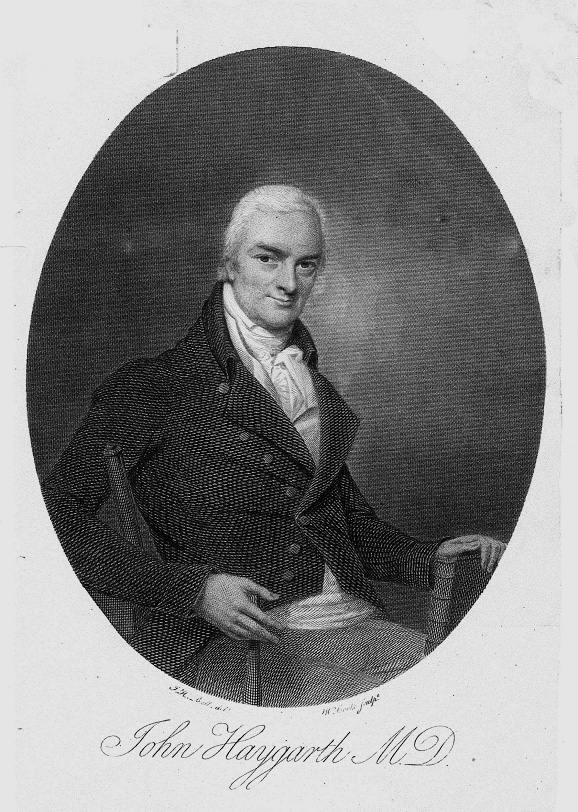

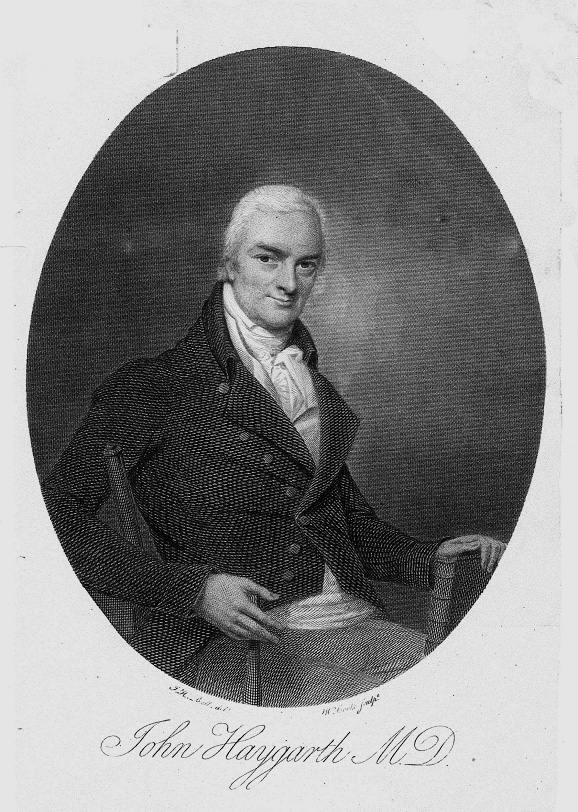

Dr Haygarth and Isolation Wards

Dr John Haygarth (1740-1827) did much to eradicate smallpox from Chester and laid the foundations of infectious disease control. As physician to the Chester Infirmary he recommended building isolation wards to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. In 1798 Haygarth retired to Bath. He acquired a house at No 15 Royal Crescent and later secured a second house on the eastern outskirts at Lambridge.

Jenner had recently published his famous paper on vaccination, and despite much initial scepticism and derision from members of the medical profession and general public, Haygarth was a firm supporter of Jenner’s discovery. Together with Thomas Creaser, a local surgeon, Haygarth helped to set up a Vaccine Institute in Bath to promote this new method of smallpox immunisation and this is thought to have been the first vaccination clinic in England.

Dr John Haygarth (1740-1827) did much to eradicate smallpox from Chester and laid the foundations of infectious disease control. As physician to the Chester Infirmary he recommended building isolation wards to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. In 1798 Haygarth retired to Bath. He acquired a house at No 15 Royal Crescent and later secured a second house on the eastern outskirts at Lambridge.

Jenner had recently published his famous paper on vaccination, and despite much initial scepticism and derision from members of the medical profession and general public, Haygarth was a firm supporter of Jenner’s discovery. Together with Thomas Creaser, a local surgeon, Haygarth helped to set up a Vaccine Institute in Bath to promote this new method of smallpox immunisation and this is thought to have been the first vaccination clinic in England.

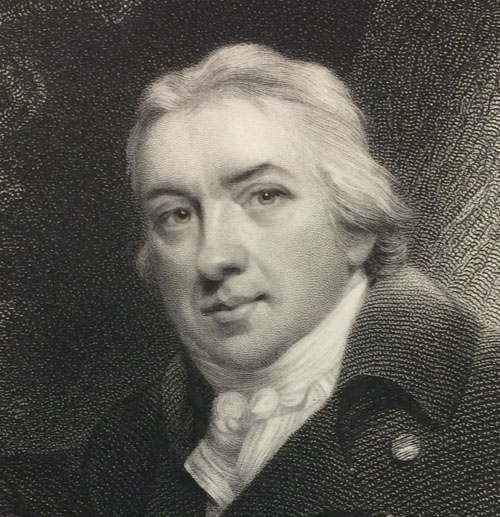

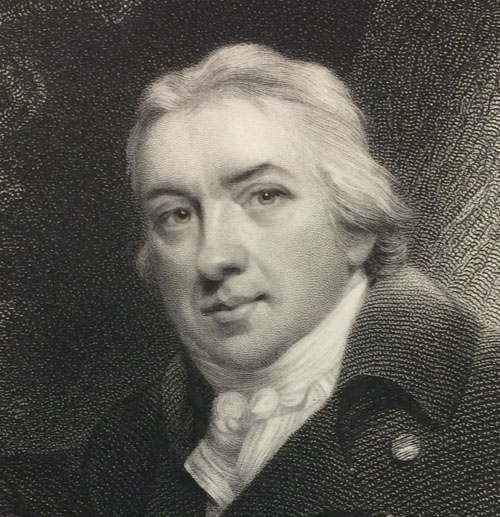

Edward Jenner and Vaccination

Major discoveries in medicine are seldom made in isolation so that a village doctor working in the depths of the English countryside engenders an almost romantic fascination by virtue of his rural situation. Edward Jenner was born in 1749 at Berkeley, Gloucestershire where his father was vicar. Orphaned at five, the boy was brought up and indulged by his elder sisters. He was apprenticed to a medical practitioner at Chipping Sodbury where he spent six years before travelling to London to enrol as a medical student under the guidance of John Hunter, whose teaching encouraged an approach to medicine through observation and experiment.

Jenner returned to practice at Berkeley where he attracted professional attention as a chemist, botanist and ornithologist, as well as continuing his interest in medical science. He was friendly with the Bath physician Caleb Hillier Parry and together they formed a small medical society where they discussed their research findings.

Major discoveries in medicine are seldom made in isolation so that a village doctor working in the depths of the English countryside engenders an almost romantic fascination by virtue of his rural situation. Edward Jenner was born in 1749 at Berkeley, Gloucestershire where his father was vicar. Orphaned at five, the boy was brought up and indulged by his elder sisters. He was apprenticed to a medical practitioner at Chipping Sodbury where he spent six years before travelling to London to enrol as a medical student under the guidance of John Hunter, whose teaching encouraged an approach to medicine through observation and experiment.

Jenner returned to practice at Berkeley where he attracted professional attention as a chemist, botanist and ornithologist, as well as continuing his interest in medical science. He was friendly with the Bath physician Caleb Hillier Parry and together they formed a small medical society where they discussed their research findings.

The rural setting was of paramount importance in the emergence of vaccination. In cities, smallpox infected so many children that there would have been an insufficient pool of susceptible people in the community to allow the protective effects of true cowpox to be observed. Conversely farm-workers, like Benjamin Jesty at Worth Matravers in Dorset, seem to have recognised the prophylactic value of cowpox long before Jenner’s publication on the subject and some, actually practised vaccination. What set Jenner apart from other aspiring vaccinators was his realisation that the rarity of natural cowpox necessitated the transfer of vesicle fluid from one human to another. It was his capacity for precise and detailed observation which characterised his real genius.

Though controversies surrounding vaccination continued to occupy him throughout the rest of his life, he became grievously melancholic from domestic worries and family deaths. The perturbation of his mind intensified like the civil unrest which gripped the country about him, and he finally died of a stroke in 1823.

Vaccination was not popular with everyone and there were lots of people who tried to discredit it. As a result, outbreaks of the disease still occurred.

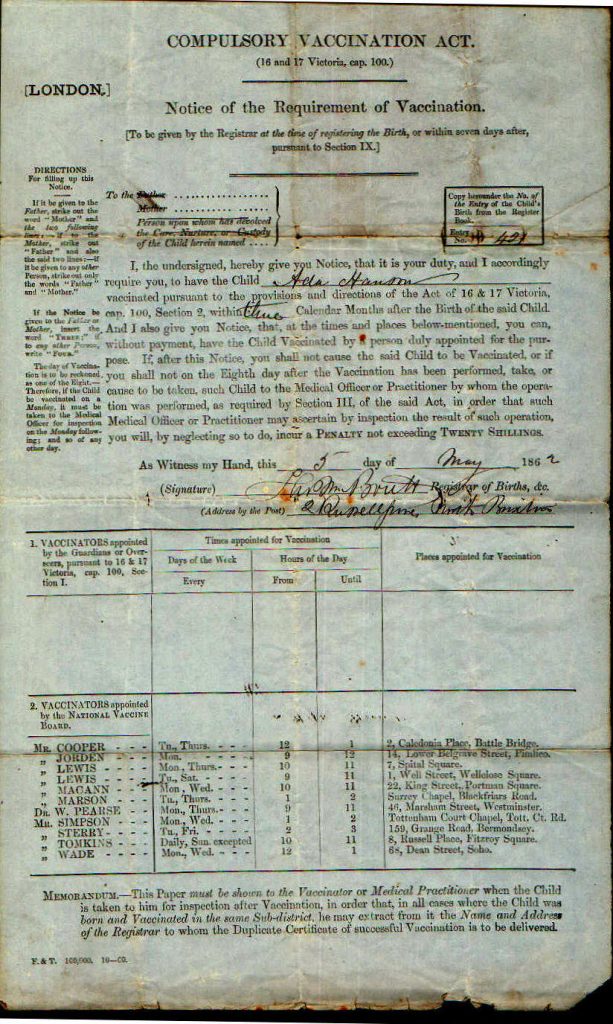

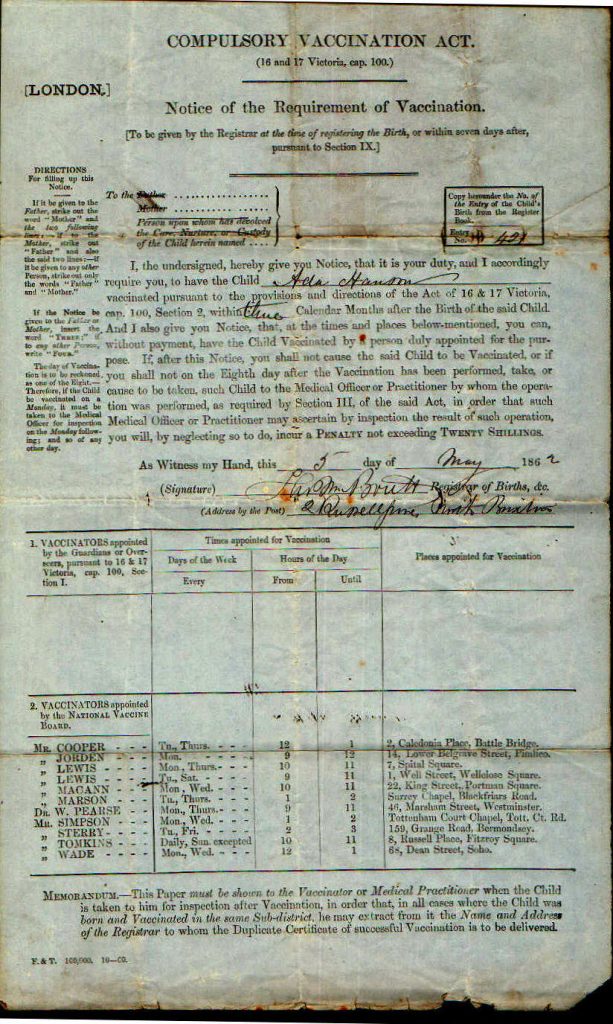

In 1853 the government introduced compulsory vaccination for all children. This was not repealed until the end of the nineteenth century when it was possible for parents who objected to their children being vaccinated to obtain a certificate of exemption.

As a result of vaccinating a large proportion of the population across the world, the World Health Organisation confirmed in 1980 that the disease had been completely eliminated from everywhere.

Though controversies surrounding vaccination continued to occupy him throughout the rest of his life, he became grievously melancholic from domestic worries and family deaths. The perturbation of his mind intensified like the civil unrest which gripped the country about him, and he finally died of a stroke in 1823.

Vaccination was not popular with everyone and there were lots of people who tried to discredit it. As a result, outbreaks of the disease still occurred.

In 1853 the government introduced compulsory vaccination for all children. This was not repealed until the end of the nineteenth century when it was possible for parents who objected to their children being vaccinated to obtain a certificate of exemption.

As a result of vaccinating a large proportion of the population across the world, the World Health Organisation confirmed in 1980 that the disease had been completely eliminated from everywhere.

Article by Dr. Roger Rolls.