One Friday in July, 1832, a young woman called Mrs. Pocock arrived back at her house on New Quay overlooking the river. She had been travelling around selling cottons and tapes. Feeling weary after a lot of walking, she put her young family to bed and wound up the evening by getting drunk. Twenty-four hours later she was dead. Dr.Edward Barlow, who was called to see her on the Saturday morning, found her in a state of extreme collapse. He was in no doubt about the diagnosis; 12 miles down river at Bristol, cholera was claiming the lives of scores inhabitants and all over Britain medical men were on the alert for the disease which was sweeping the country.

The pandemic of cholera which had originated in Bengal in 1817 had reached Sunderland in October, 1831. Since that day the disease had caused whole towns to empty in terror and ravaged the populace of the country like nothing else since the plague. The West Country was the last corner of England to be visited by this devastating epidemic. Compared with Bristol and Exeter, Bath escaped lightly but none the less seventy-four cases were notified between July and October of 1832, and forty-nine of these ended in death.

Following the death of Mrs. Pocock, the Mayor of Bath convened a meeting to formulate a plan for managing the pandemic. Even before the weekend had passed, a second case had been notified. A carter called Tom Smith residing at Ferry Place in the Dolemeads fell ill after eating a meal of raw cucumbers, and died within a few hours.

The council quickly set up a Board of Health which was to be notified dally of new cases arising in each parish. Plans were drawn up to check the progress of the disease. Burial places were appointed exclusively for cholera victims. In Walcot, one corner of the parish cemetery was walled off. Sentries were employed to guard the city entrances and control the ingress of travellers. Vagrants’ lodging houses were closely scrutinised. Wherever cases occurred, all clothing and bedding of the victims was burnt and the rooms of the houses fumigated and whitewashed.

Victims had to be buried within 48 hours of death, and before eight in the morning. Early burial was enforced in order to avoid attracting too much attention in the neighbourhood. It was feared that contagion might spread from the corpse and the authorities were anxious to avoid generating alarm. The Board resolved that publicity should be avoided as far as possible. Only medical men and officials immediately involved were to be informed about the course of the disease. The Board feared that once the press got wind of an epidemic in the city, unnecessary panic would be generated amongst the citizens and wealthy visitors who frequented Bath during the summer months would be discouraged from visiting. That would mean a financial loss to businesses relying on their presence. Under normal circumstances local boards of health were required to send a weekly statistical report to the Central Board in London during an outbreak. Because these figures were published in the national press, the council failed to comply with this ruling.

Victims had to be buried within 48 hours of death, and before eight in the morning. Early burial was enforced in order to avoid attracting too much attention in the neighbourhood. It was feared that contagion might spread from the corpse and the authorities were anxious to avoid generating alarm. The Board resolved that publicity should be avoided as far as possible. Only medical men and officials immediately involved were to be informed about the course of the disease.

The Board feared that once the press got wind of an epidemic in the city, unnecessary panic would be generated amongst the citizens and wealthy visitors who frequented Bath during the summer months would be discouraged from visiting. That would mean a financial loss to businesses relying on their presence. Under normal circumstances local boards of health were required to send a weekly statistical report to the Central Board in London during an outbreak. Because these figures were published in the national press, the council failed to comply with this ruling.

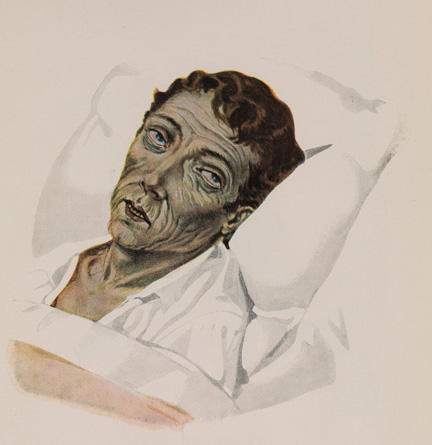

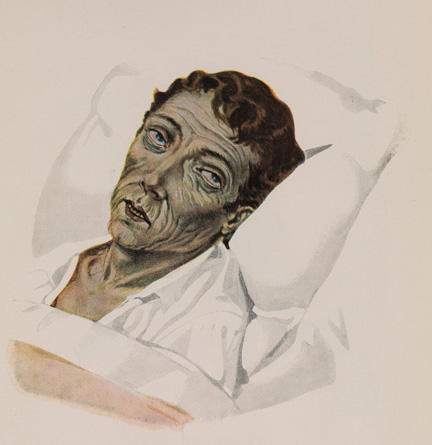

Nearly 3 weeks passed after the first two deaths before any further cases were reported in the city. A GP, Mr Ogilvie, was called to see a woman living in Lower Bristol Road. She was the mother of four children, the youngest of whom she was breastfeeding. She had developed diarrhoea in the previous week and by the time Mr Ogilvie arrived she was desperately ill. He reported “It was nearly 12 o’clock on Thursday when I first saw her, and she was then in a state of complete collapse; extremities cold, and suffused with a copious serous exudate” Her pulses were undetectable, her eyes sunk and her skin was the colour of slate. By 6pm she was dead.

The number of cases began to accelerate. A destitute boy called Isaac Davies had recently come from Bristol and was picked up by the police and sent to a lodging house where he later died. A woman called Jane Franks, developed diarrhoea and a doctor was called to see her. He thought she had “summer enteritis” but early the following morning she was much worse. Another doctor was called at 5 am. He found her “screaming in pain from cramps in her legs, so violent as nearly to double them close to her body“. She was severely dehydrated and there was a blue discolouration of her body. She was dead before noon.

The Board were notified and preparations made to bury the body under the emergency regulations. On learning that his wife’s body was to be disposed of in this manner, the husband and other relations refused to allow the body to be removed from the house, insisting on their rights to have the usual ceremonies carried out. After much argument they eventually agreed to an emergency funeral.

Difference of opinion between doctors about the diagnosis did nothing to improve public confidence in the medical profession who lacked any success in treating the disease. When cholera broke out in the nearby village of Camerton, the Rector John Skinner had little respect for the treatment offered by the local practitioners. “Mr Curtis says he finds bleeding the most efficacious remedy and says he is pretty confident he can stop it if called in at the first but it seems that out of nine cases the whole lot perished.“

The measures taken to prevent spread of infection were no more effective than the treatment. John Snow’s discovery that cholera was spread in contaminated water was not published until twenty years later. Until then the mode of infection was entirely speculative, with argument over whether the cause was from contact with bad air (miasma) or contagious material. The preventive strategies of previous pandemics were resurrected: bonfires were lit in the streets, bodies and bedclothes were soused with vinegar, rooms were fumigated by burning tar, tobacco and old ropes, and vinegar and spirits of camphor were poured around in liberal quantities. Infected houses were hurriedly whitewashed with quicklime.

After considerable disagreement amongst its members, the Board decided to set up a cholera isolation hospital. Besides financing the hospital, funds were needed for cholera reception centres where medicines could be dispensed and medical advice given. Other expenses included the cost of funerals and compensation for clothing and bedding which had to be burned. Scavenging and whitewashing also cost money.

The obvious source of funding was from the parish Poor Rate. Each of the six city parishes was approached. The board needed a total of £510. Walcot, the largest parish, refused to pay its share, considering £250 too high. The Board, now desperate for funds, approached the national government for a mandate to obtain the money. The government consulted the statistics of the Central Board of Health only to find that the figures for Bath showed a remarkably mild epidemic. The Bath Board were informed that the amount they applied for was too much “at so early a stage of the disease“. Bath’s failure to report all its cases to the Central Board backfired and it required some embarrassed grovelling to get the mandate they required.

Meanwhile, the epidemic with raging in the slum areas near the river. By the end of August every lodger at 27 Avon Street had died of the disease. The landlady, Charlotte Sidnell, having attended all her tenants in their death throes finally succumbed in the first week of September. Her husband was the only remaining occupant and he quickly left. The now vacant property was commandeered to provide a reception centre for cholera victims.

The Board was still trying to establish its isolation hospital but encountered considerable opposition from owners of suitable premises for obvious reasons. Nobody wanted to risk possible contamination. Every time an empty house was earmarked by the Board it would mysteriously fill up with occupants and the Board was forced to look elsewhere. At last they found an empty timber shed situated off the Upper Bristol Road which served their purpose but by the time it was fitted out the epidemic was nearly over.

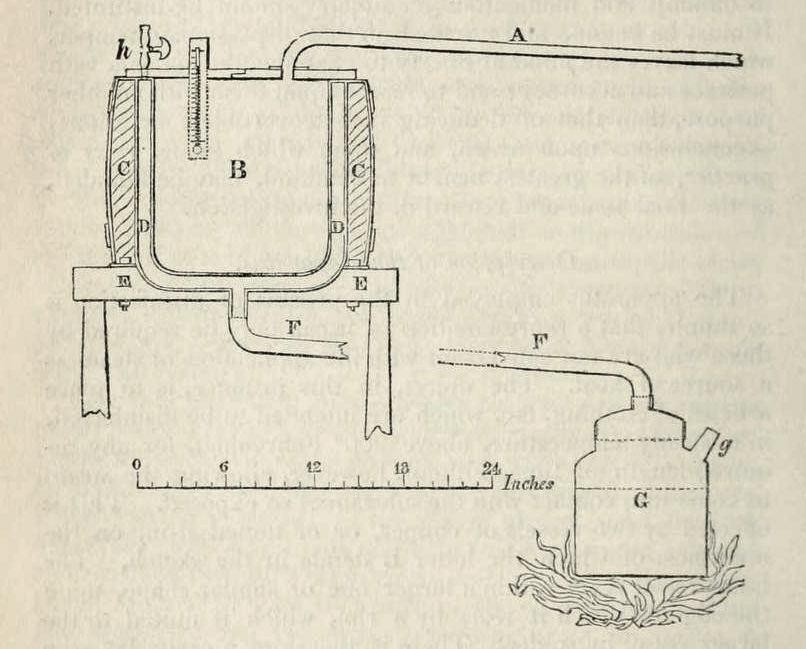

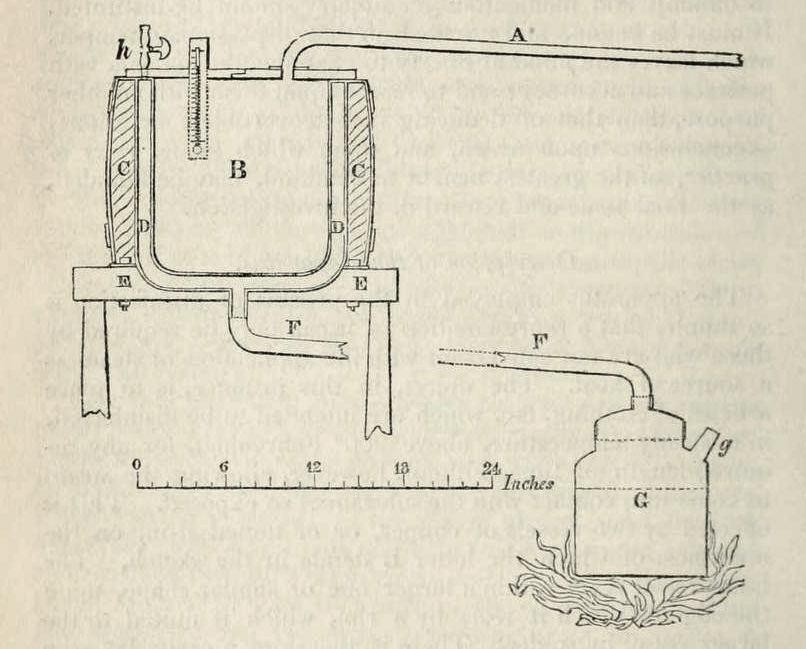

The decision to burn all infected clothes and bedding was proving expensive in compensation money. A Manchester physician, Dr. William Henry invented a new method for sterilising clothes using steam. Although the Board was interested in his apparatus nobody was prepared to fund it so the burning continued.

The last case of cholera was recorded on October 17 and the Board declared the city free of disease six days later. The shed which had been taken over as a cholera hospital was returned to its owner and the nurses dismissed. The reception centre in Avon Street was closed. In retrospect the most evident feature of the epidemic noted by the Board was its virtual confinement to one part of the city. Bordering on both banks of the river this locality was inhabited by poorer people many of whom were vagrants and tramps. The water supply to this part of town, according to a report in 1845, was available only from stand-pipes in the road which were turned on at certain times of the day. Although fresh water was sold from water carts, poor people living so near the Avon found it both easier and cheaper to fetch their water from the river into which the effluent of the city discharged. Interestingly the first two cases occurred upstream from the main centre of the epidemic. Three more cholera epidemics occurred throughout the country in the middle of the 19th century but Bath escaped lightly.

The last case of cholera was recorded on October 17 and the Board declared the city free of disease six days later. The shed which had been taken over as a cholera hospital was returned to its owner and the nurses dismissed. The reception centre in Avon Street was closed. In retrospect the most evident feature of the epidemic noted by the Board was its virtual confinement to one part of the city.

Bordering on both banks of the river this locality was inhabited by poorer people many of whom were vagrants and tramps. The water supply to this part of town, according to a report in 1845, was available only from stand-pipes in the road which were turned on at certain times of the day. Although fresh water was sold from water carts, poor people living so near the Avon found it both easier and cheaper to fetch their water from the river into which the effluent of the city discharged. Interestingly the first two cases occurred upstream from the main centre of the epidemic. Three more cholera epidemics occurred throughout the country in the middle of the 19th century but Bath escaped lightly.

This article by Dr. Roger Rolls is based on “Mainwaring’s Narrative” published by Meyler , Bath. 1833.