Bubonic plague, caused by Yersinia Pestis, is characterised by swollen lymph glands (buboes) in the groin and armpits, fever, prostration, and skin haemorrhages. The disease is primarily a zoonotic infection – ie: a disease of animals. It affects rodents, rats being the primary reservoir of infection. As such, the disease in the 16th and 17th centuries was enzootic (i.e. continuously present at a low level in the rodent population). Most rats survived and became immune. Why then did plague breakout amongst humans living in cities like Bath?

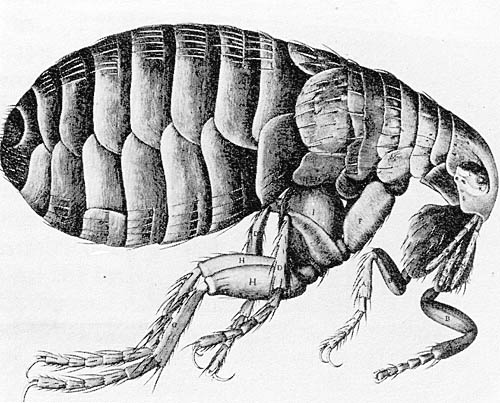

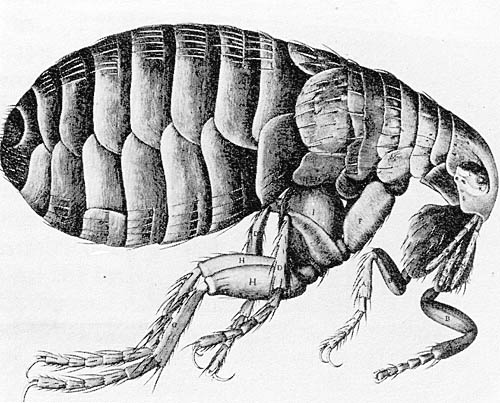

The diseases is transmitted between rats by fleas. The most efficient plague vector is a flea called xenopsylla cheopis. This flea lives on the black rat, a species much more prevalent in the 16th and17th centuries. The black rat population was reduced quite dramatically in the second half of the 17th century, superseded by the brown rat which does not live in such a close association with man.

Rat fleas will only turn to humans when rats die. This could occur following an epizootic of plague, or when climatic changes or food shortages threaten the normal survival of rats. Human fleas seldom carried the disease, but might do in unhygienic and crowded circumstances.

The diseases is transmitted between rats by fleas. The most efficient plague vector is a flea called xenopsylla cheopis. This flea lives on the black rat, a species much more prevalent in the 16th and17th centuries. The black rat population was reduced quite dramatically in the second half of the 17th century, superseded by the brown rat which does not live in such a close association with man.

Rat fleas will only turn to humans when rats die. This could occur following an epizootic of plague, or when climatic changes or food shortages threaten the normal survival of rats. Human fleas seldom carried the disease, but might do in unhygienic and crowded circumstances.

There is a popular misconception both now and in the 17th century that plague swept the country like wildfire. If there was a countrywide epidemic, we should also expect to see increased mortality in 1563, 1578, 1593 all of which were years of plague in London. There were no Bath epidemics in these years. However, there was possibly some correlation with London plague years in 1582, 1603 and 1625, the Bath outbreaks being a year later except for 1625. The Bath council was aware of the danger of allowing visitors into the city who had come from places where plague was active. For instance, the Chamberlain’s account for 1583 records paying two sentries to turn away visitors from Paulton where there was a plague outbreak. After the London outbreak of 1625 the council arranged for plague quarantine houses to be made available in Bath but the expected outbreak did not occur.

In 1636, houses were built on the Common for isolating plague victims. There was no increase in burials in the Abbey records for that year so isolation may have been a successful way of reducing the death rate, but it is more likely that the expected epidemic did not happen…

Burial records give information about the number of deaths but not usually about causation. Plague was not the only killer disease around. Sir William Brereton reported a smallpox outbreak “raged exceedingly” in Bath in July 1635. Other potential epidemics which could have been associated with a high mortality are: measles, typhus, typhoid and respiratory viruses like influenza.

The Bath Abbey records show an increased mortality occurring in the year 1604 and there is some correspondence between Lord Burleigh and Dr. Sherwood, a Bath physician, in which the doctor advises Burleigh not to visit the city on account of plague. A bill of mortality for that year corroborates this.

The Bath authorities appear to have feared the spread of plague from London in 1665 because no person was allowed into the city from the capital without special permission of the mayor and justices, and nobody at all was allowed in between 10 pm and 5 am. Sentries were posted on the routes into town to police these regulations. Any Bath citizens who received guests coming from London was fined £10. This strategy may have been successful because there was no evidence of increased mortality in that year.

After 1665 the number of plague cases dwindled and there were no more major outbreaks of the disease in Bath. There are various theories why plague disappeared from Great Britain. The most widely accepted is the replacement of the black rat by the brown species which kept greater distance from humans although there may be other reasons.

The Bath Abbey records show an increased mortality occurring in the year 1604 and there is some correspondence between Lord Burleigh and Dr. Sherwood, a Bath physician, in which the doctor advises Burleigh not to visit the city on account of plague. A bill of mortality for that year corroborates this.

The Bath authorities appear to have feared the spread of plague from London in 1665 because no person was allowed into the city from the capital without special permission of the mayor and justices, and nobody at all was allowed in between 10 pm and 5 am. Sentries were posted on the routes into town to police these regulations. Any Bath citizens who received guests coming from London was fined £10. This strategy may have been successful because there was no evidence of increased mortality in that year.

After 1665 the number of plague cases dwindled and there were no more major outbreaks of the disease in Bath. There are various theories why plague disappeared from Great Britain. The most widely accepted is the replacement of the black rat by the brown species which kept greater distance from humans although there may be other reasons.

Article by Dr. Roger Rolls.