It is easy to forget how much illness and death was caused by infectious disease in former times. In 1896 a quarter of people in Bath catching diphtheria died from it. Add to this deaths from smallpox, measles and scarlet fever and it is hardly surprising that most families lost at least one child under the age of ten.

The idea of isolating patients suffering from infectious fevers in special hospital wards or confining them to their own homes was recognised at the end of the 18th century by Dr John Haygarth who retired to Bath from Chester and practised in the city for 30 years. His views were embodied in letters he wrote to British and American doctors which were read to the Bath Philosophical Society.

It is easy to forget how much illness and death was caused by infectious disease in former times. In 1896 a quarter of people in Bath catching diphtheria died from it. Add to this deaths from smallpox, measles and scarlet fever and it is hardly surprising that most families lost at least one child under the age of ten.

The idea of isolating patients suffering from infectious fevers in special hospital wards or confining them to their own homes was recognised at the end of the 18th century by Dr John Haygarth who retired to Bath from Chester and practised in the city for 30 years. His views were embodied in letters he wrote to British and American doctors which were read to the Bath Philosophical Society.

It took Bath City Council over seventy more years to establish a special hospital for isolating patients with infectious diseases. Its name derived from the statutory powers conferred by the Public Health Act of 1875. Bath had one of the first of many isolation hospitals which were to be constructed in towns and cities throughout the country.

The hospital occupied a site of about 8 acres on Claverton Down on the summit of Brass Knocker Hill. A house and a gardener’s cottage were purchased in 1876. The first patient was admitted in October 1876 suffering from scarlet fever. Two small and two large wooden pavilions were added on the south side of the house providing a total hospital accommodation for 70 patients together and some resident staff.

It took Bath City Council over seventy more years to establish a special hospital for isolating patients with infectious diseases. Its name derived from the statutory powers conferred by the Public Health Act of 1875. Bath had one of the first of many isolation hospitals which were to be constructed in towns and cities throughout the country.

The hospital occupied a site of about 8 acres on Claverton Down on the summit of Brass Knocker Hill. A house and a gardener’s cottage were purchased in 1876. The first patient was admitted in October 1876 suffering from scarlet fever. Two small and two large wooden pavilions were added on the south side of the house providing a total hospital accommodation for 70 patients together and some resident staff.

Smallpox Outbreak

There was an outbreak of smallpox in 1903 when twelve patients and one ward maid at the Mineral Water Hospital caught the disease. These patients were isolated in two wooden ‘tents’, made by the Berthon Boat Company. The tents were 21 feet in diameter with conical canvas roofs and circular concrete bases. Ventilation was by fresh air entering between the double sides, and escaping through ventilators at the apex. The tents were heated by slow combustion stoves located in their centres, with a stove pipe projecting through the apex. They frequently leaked and were removed from the site in 1911.

Smallpox Outbreak

There was an outbreak of smallpox in 1903 when twelve patients and one ward maid at the Mineral Water Hospital caught the disease. These patients were isolated in two wooden ‘tents’, made by the Berthon Boat Company.

The tents were 21 feet in diameter with conical canvas roofs and circular concrete bases. Ventilation was by fresh air entering between the double sides, and escaping through ventilators at the apex. The tents were heated by slow combustion stoves located in their centres, with a stove pipe projecting through the apex. They frequently leaked and were removed from the site in 1911.

Patients’ clothes were sterilised in a Washington Lyons high pressure steam disinfector, purchased for £430, a not inconsiderable sum in those days. The permanent staff consisted of one head nurse, three assistant nurses, four servants, and a porter and his wife . More permanent staff were taken on in 1902 and extra nurses were engaged when required. After 1901 the term head nurse was replaced by matron.

Before the first world war, nurses had been obliged to use the same baths as the patients and lacked any separate accommodation. This was remedied by adding an extension on the east side of the old house which provided 14 extra bedrooms and two bathrooms.

The hospital was administered by the city council’s Sanitary Committee. From 1878 until his death in 1905, a Bath general practitioner called Dr Field provided clinical care for the patients. He was replaced by Dr William Collins, another Bath G.P.

Patients were originally conveyed to the hospital in a horse drawn ambulance, a driver and horse being provided when needed by tradesmen in Kensington. In 1932, the hospital acquired a 20 horsepower Austin ambulance which was garaged in the hospital grounds.

The hospital was administered by the city council’s Sanitary Committee. From 1878 until his death in 1905, a Bath general practitioner called Dr Field provided clinical care for the patients. He was replaced by Dr William Collins, another Bath G.P.

Patients were originally conveyed to the hospital in a horse drawn ambulance, a driver and horse being provided when needed by tradesmen in Kensington. In 1932, the hospital acquired a 20 horsepower Austin ambulance which was garaged in the hospital grounds.

In the early days, admissions were largely for cases of scarlet fever and diphtheria. Between 1895 and 1899, there was annual average admission rate of 137 of which 78% were patients with scarlet fever and 22% diphtheria. Only 7 out of 137 were for other conditions, for example smallpox. Before 1900, many doctors did not always insist on admission of infectious cases to the hospital but attitudes changed in the early twentieth century. Between 1895 and 1900, only 41% of known diphtheria cases were admitted whereas between 1940 and 1945, 97% were removed from home to hospital.

Most of the patients were children. The rules for visiting were strict and especially as patients were often kept in the hospital for up to two months. Visitors were warned that they ran a great risk of infection and were advised not to travel on public transport when leaving the hospital.

In the early days, admissions were largely for cases of scarlet fever and diphtheria. Between 1895 and 1899, there was annual average admission rate of 137 of which 78% were patients with scarlet fever and 22% diphtheria. Only 7 out of 137 were for other conditions, for example smallpox. Before 1900, many doctors did not always insist on admission of infectious cases to the hospital but attitudes changed in the early twentieth century.

Between 1895 and 1900, only 41% of known diphtheria cases were admitted whereas between 1940 and 1945, 97% were removed from home to hospital.

Most of the patients were children. The rules for visiting were strict and especially as patients were often kept in the hospital for up to two months. Visitors were warned that they ran a great risk of infection and were advised not to travel on public transport when leaving the hospital.

Scarlet Fever

Scarlet fever was the predominant condition treated in the hospital through most of its history. Formerly, this was a common and often fatal consequence of streptococcal tonsillitis. In 1864, one in two hundred and fifty persons in Bath died of the disease. By the mid twentieth century the severity of the condition had waned with a dramatic fall in the death rate, although there was no corresponding fall in the incidence of infection. Nobody is sure of why this decline in virulence occurred. It was showing a downward trend before the advent of isolation hospitals and had virtually disappeared by the time antibiotics came on the scene after the second world war.

Diptheria

An effective treatment for diphtheria using an antitoxin first became available after 1895 and was regularly used at the hospital from 1898 for both definite and suspected cases, as well as cases treated at home. This resulted in a dramatic fall in the death rate from around 20% before 1900 to less than 4% by the 1920s. By the mid 1920s, immunisation using diphtheria toxoid became available but there was great reluctance for parents in Bath to get their children protected by this method. At the end of 1944, it was estimated that there were still 50% of children in Bath who had not been immunised against diphtheria.

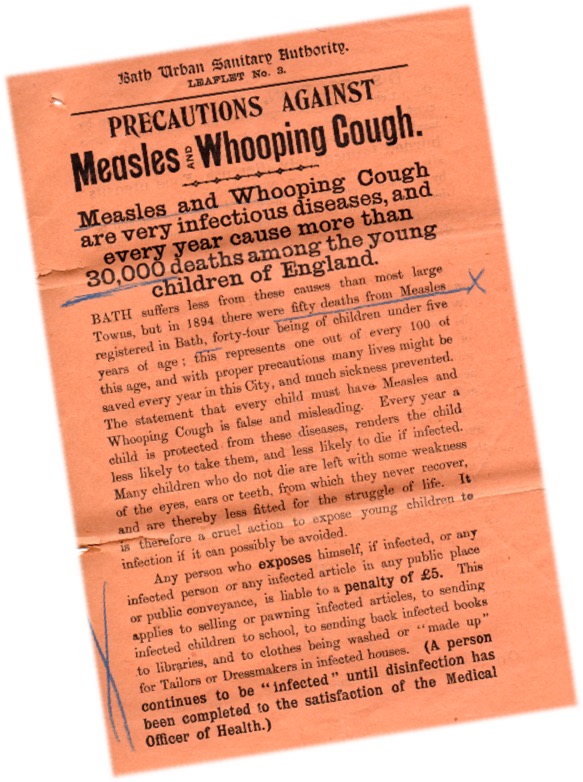

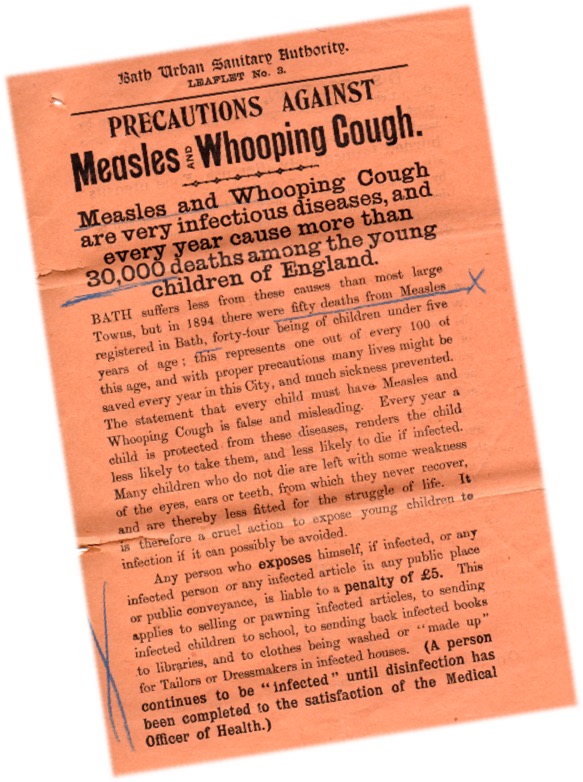

Measles

Measles has also waned in virulence. Until well into the twentieth century, between 30 and 50 Bath children died of the disease during an epidemic year. In the first half of 1915, over 12000 deaths from measles were recorded in the UK, a statistic which greatly worried Local Government Health Boards. It was a notifiable disease; all cases had to be reported to the Medical Officer of Health. Failure to do so resulted in a fine of £100, a colossal amount by today’s standards.

People suffering from the disease were also fined if they travelled on pubic transport and parents could be fined for sending infected children to school. The MOH for Bath requested that the Board of Guardians for the Frome Road Workhouse (later St Martin’s Hospital) allow a block of buildings next to the Workhouse Infirmary to be used as a temporary ward for children with measles. As it turned out, despite 1916 and 1917 being epidemic years, little use was made of these wards and future cases requiring hospital treatment were admitted to the Statutory Hospital.

Measles

Measles has also waned in virulence. Until well into the twentieth century, between 30 and 50 Bath children died of the disease during an epidemic year. In the first half of 1915, over 12000 deaths from measles were recorded in the UK, a statistic which greatly worried Local Government Health Boards. It was a notifiable disease; all cases had to be reported to the Medical Officer of Health. Failure to do so resulted in a fine of £100, a colossal amount by today’s standards.

People suffering from the disease were also fined if they travelled on pubic transport and parents could be fined for sending infected children to school. The MOH for Bath requested that the Board of Guardians for the Frome Road Workhouse (later St Martin’s Hospital) allow a block of buildings next to the Workhouse Infirmary to be used as a temporary ward for children with measles. As it turned out, despite 1916 and 1917 being epidemic years, little use was made of these wards and future cases requiring hospital treatment were admitted to the Statutory Hospital.

New Hospital

In 1924, the decision was taken to demolish the old wooden ward blocks and replace them with stone built pavilions but construction did not commence for another six years. The new hospital was finally completed in October 1934. The only parts of the earlier hospital left standing were a wing of the original house and the “discharge” block which was used for isolating highly contagious patients

There were three pavilions, two for scarlet fever patients and one for diphtheria cases although some flexibility of use was necessary as other infectious diseases requiring isolation were sometimes admitted.

In 1924, the decision was taken to demolish the old wooden ward blocks and replace them with stone built pavilions but construction did not commence for another six years. The new hospital was finally completed in October 1934. The only parts of the earlier hospital left standing were a wing of the original house and the “discharge” block which was used for isolating highly contagious patients.

There were three pavilions, two for scarlet fever patients and one for diphtheria cases although some flexibility of use was necessary as other infectious diseases requiring isolation were sometimes admitted.

The Statutory Hospital was taken over by the NHS in 1948 and renamed Claverton Down Hospital. For some years it continued in its role as an infectious diseases hospital and treated many children with poliomyelitis during the epidemics of the early post war years. The hospital purchased a number of Drinker respirators, popularly known as iron lungs. After the introduction of poliomyelitis vaccination, there were no further cases fell the artificial respirators were removed.

With the declining virulence of scarlet fever and effective immunisation programmes against the common childhood epidemic diseases, there was little need for an isolation hospital. In the 1970s a few patients with tuberculosis were treated there and for a brief period the hospital provided accommodation for patients with respiratory diseases after the closure of Winsley Hospital in 1977. In the final years prior to its closure, it also acted as an overspill for elderly patients from St Martin’s Hospital.

In 1986, the Wessex Regional Health Authority decided to close the hospital and accommodate the relatively few infectious disease cases in an isolation ward at Bath’s Royal United Hospital. The Claverton Down site lay derelict until 1997 when Wessex Water acquired the site. In February 1999 planning permission was granted and all the hospital’s buildings were demolished. The site now accommodates the administrative offices of Wessex Water and which were completed in July 2000. No trace of the hospital survives.

Article by Dr. Roger Rolls.