In 1806, the Bath Chronicle reported that “a kind of influenza that spares no one at present prevails in Spain. Fortunately, it is seldom fatal. The whole of the Royal Family have been attacked by it. At Barcelona where this malady commenced, 28,300 persons were ill of it at once.” This is not the Spanish Flu we talk of now but an epidemic which occurred over a hundred years earlier.

Pandemics of acute respiratory infections have occurred regularly over the past few centuries. The best known and most devastating occurred at the end of the First World War leading to an estimated mortality of sixty million people worldwide. We now know the cause was a virus known as influenza A H1N1. In 1917 no one had ever seen a virus as they were too small to be viewed with an optical microscope. Few people then had any idea of what was causing it.

In the 1880s, Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and other scientists had discovered that many infectious diseases were caused by bacteria but they could not find microbes to explain the cause of all of them. Foot and Mouth disease was one example. In 1898 two German scientists, Friedrich Loeffler and Paul Frosch collected material from a cow with the disease, added it to some sterile fluid and passed it through a ceramic filter to remove bacteria. They found the filtered fluid could still infect other cows, proving that it must contain something infectious that was smaller than bacteria. Whereas most scientists assumed this infectious agent could be a dissolved poison (the word ‘virus’ originally meant poison), Loeffler and Frosch suggested the fluid might contain particles so small that they were invisible even with a high-powered microscope. They were eventually proved correct, but it was not until the invention of the electron microscope in the 1930s that the structure of these microorganisms could be finally visualised.

Even in 1920, there was still considerable doubt about the causative agent of influenza, an illness with a history spanning many centuries. The name derives from the Italian ‘influensia’ and refers to the old idea that feverish coughs and colds which appeared from time to time were influenced by the weather and cosmic events because of their apparent seasonal relationship.

Mostly these illnesses produced mild symptoms but every now and then they struck, like the Spanish flu, with unusual ferocity killing lots of people over a short period. There are clinical accounts of earlier influenza epidemics and pandemics with comprehensive descriptions of symptoms resembling a flu-like illness. We cannot be sure that all earlier epidemics, despite being labelled as influenza, were caused by the influenza virus. From our experience of the current pandemic caused by a coronavirus, Covid-19 produces symptoms very similar to influenza including serious lung complications.

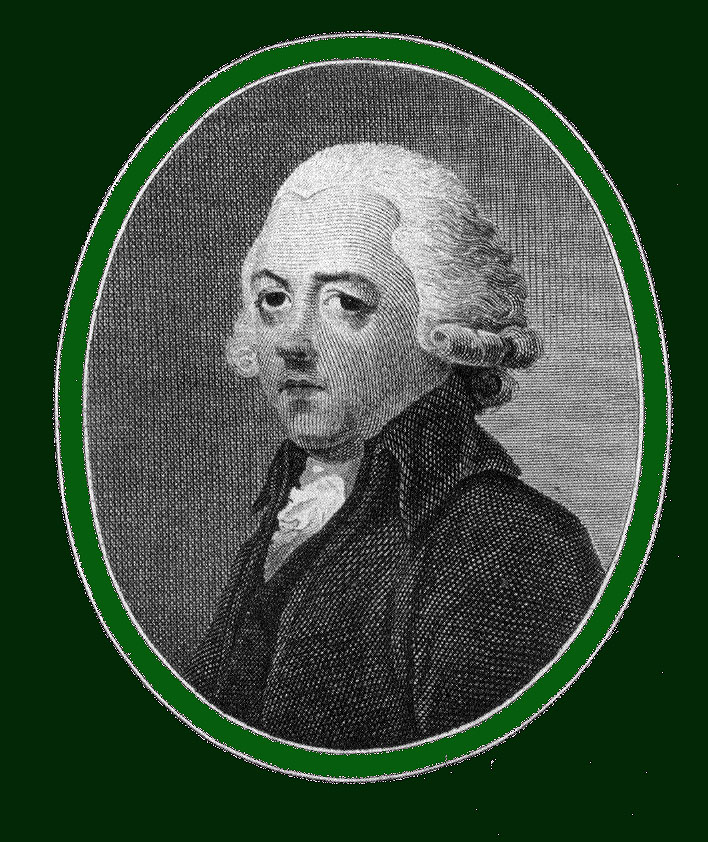

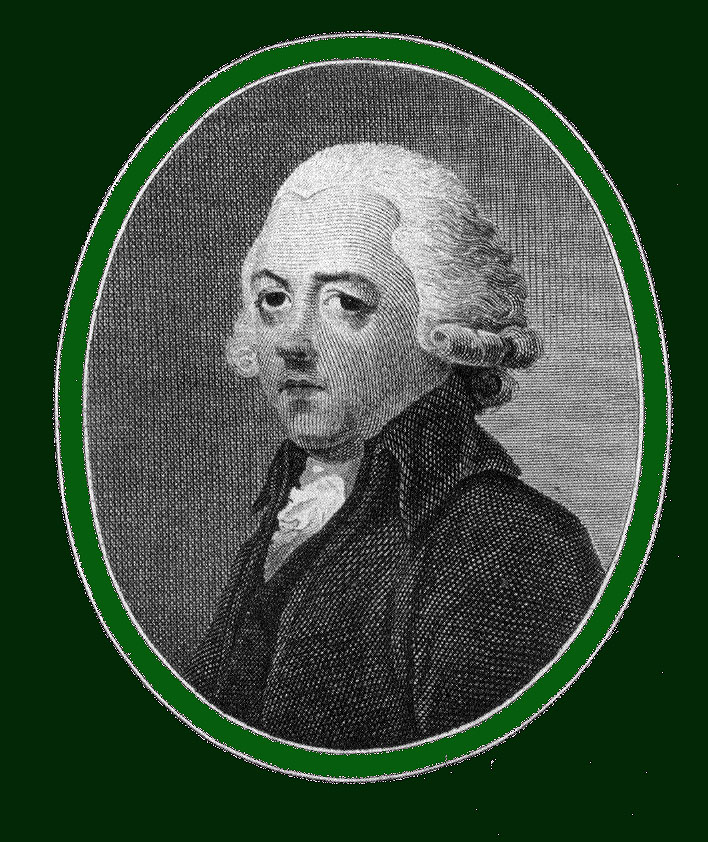

We have only recently been able to accurately identify the type of virus causing flu-like pandemics. This was not the case in earlier centuries. For most of the 18th century, doctors believed that influenza was caused by miasmas – polluted air, cold and damp environments, and excremental odours. It was largely the work of two doctors, John Haygarth and William Falconer, working collaboratively in Chester and Bath that the contagious nature of influenza was recognised. Haygarth presciently wrote in 1803 that “it might be difficult to exterminate the influenza from any country, because it spreads so quickly and universally through all ranks of people, being attended with little danger to the generality of mankind. But as the influenza is fatal to patients ill of many other diseases, or debilitated by age, it is certainly of much importance to know that such persons may be preserved from the contagion by cautious separation, so as to prevent every patient ill of the distemper from approaching them; and by strict cleanliness, so that no dirty clothes, etc, which can contain infection, may be brought to them.”

Haygarth believed that contagious diseases could be prevented by isolation. He set up specific fever wards in Chester General Infirmary to protect other patients in the hospital. He recommended home isolation for persons with smallpox. His ideas were developed in the nineteenth century when special isolation hospitals were built in towns and cities to accommodate patients, usually children, suffering from contagious diseases like measles, scarlet fever and diphtheria although influenza was usually treated at home. If patients developed pneumonia there was little to be gained from hospital admission and they either survived or died at home.

Dr. William Falconer described the influenza pandemics of 1782 and 1803 which he witnessed in Bath. Whereas there were few fatalities in the earlier epidemic despite large numbers of all ages being affected, the 1803 winter epidemic appears to have been more severe with more lung complications and a higher death rate which is reflected in an increase of church burial figures. Falconer’s treatment reflects the long held view that bloodletting was beneficial in treating fevers. He was convinced that if patients could be bled in the initial stages of the disease, they could avoid the pulmonary complications. It is difficult to conceive today how this could have given any benefit.

Lack of effective treatment was just as evident in the “Spanish” influenza pandemic a century later. Although we now have vaccines to provide protection against seasonal influenza, newly mutated viruses like Covid-19 still present a therapeutic challenge. Fortunately we are in a better position than doctors in 1917 who lacked intensive care facilities and had no antibiotics for treating secondary bacterial infections.

Dr. William Falconer described the influenza pandemics of 1782 and 1803 which he witnessed in Bath. Whereas there were few fatalities in the earlier epidemic despite large numbers of all ages being affected, the 1803 winter epidemic appears to have been more severe with more lung complications and a higher death rate which is reflected in an increase of church burial figures. Falconer’s treatment reflects the long held view that bloodletting was beneficial in treating fevers. He was convinced that if patients could be bled in the initial stages of the disease, they could avoid the pulmonary complications. It is difficult to conceive today how this could have given any benefit.

Lack of effective treatment was just as evident in the “Spanish” influenza pandemic a century later. Although we now have vaccines to provide protection against seasonal influenza, newly mutated viruses like Covid-19 still present a therapeutic challenge. Fortunately we are in a better position than doctors in 1917 who lacked intensive care facilities and had no antibiotics for treating secondary bacterial infections.

At the end of World War I food was scarce and was still rationed although this was more of a problem in Germany than the UK. Ventilators had not been invented to treat lung complications and most of the male population smoked. Many men had been debilitated both physically and mentally from their harrowing experience in the war. Demobilisation led to troops being crowded together on trains and in tents. In the desire to celebrate the end of hostilities, little effort was made to isolate patients when they contracted the disease so it spread rapidly through the community. Figures collected in Bath show that the epidemic peaked between October and December 1918 with a death rate of 3.25 per hundred, which was about three times the death rate for the city during the previous year. A few sporadic cases occurred in 1919. When the MOH was asked by a councillor if any preparations were made in case a more severe epidemic broke out again, he answered “You cannot anticipate it- if it comes, it comes”

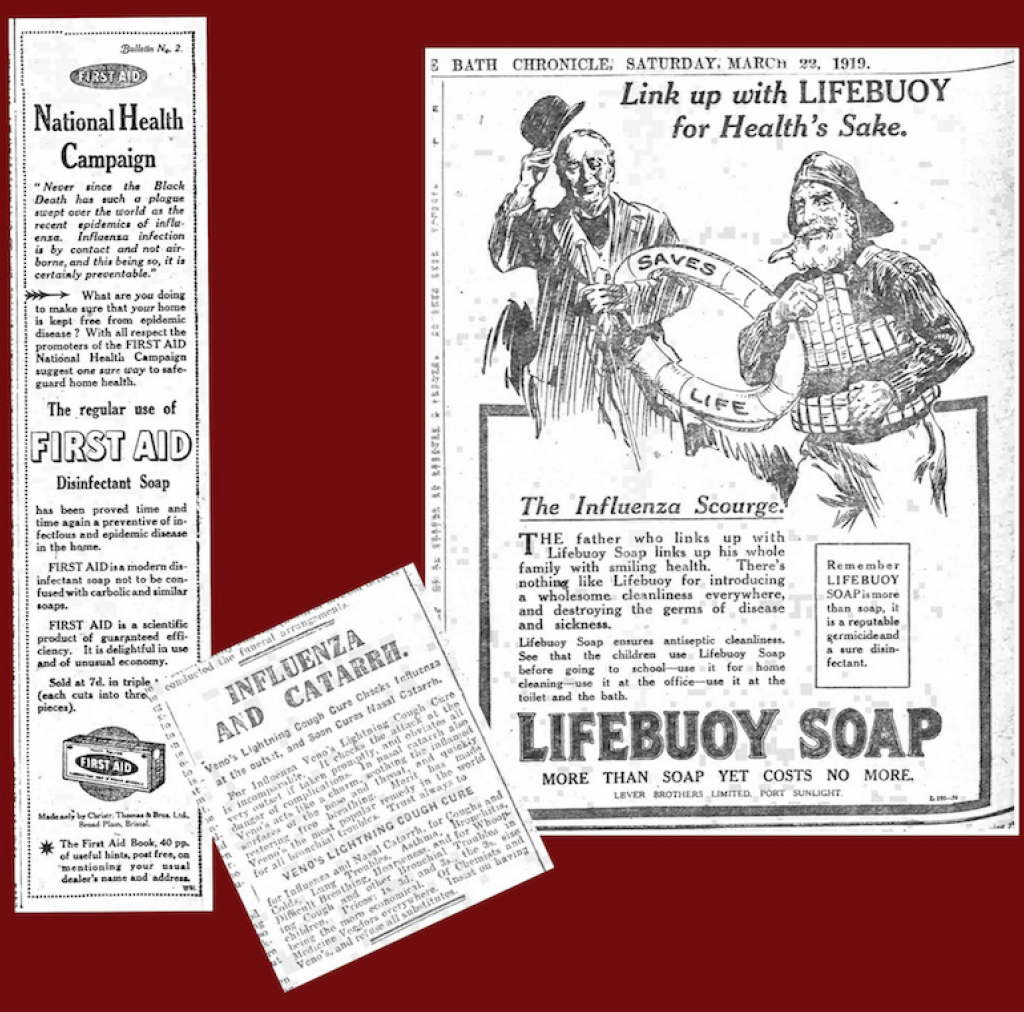

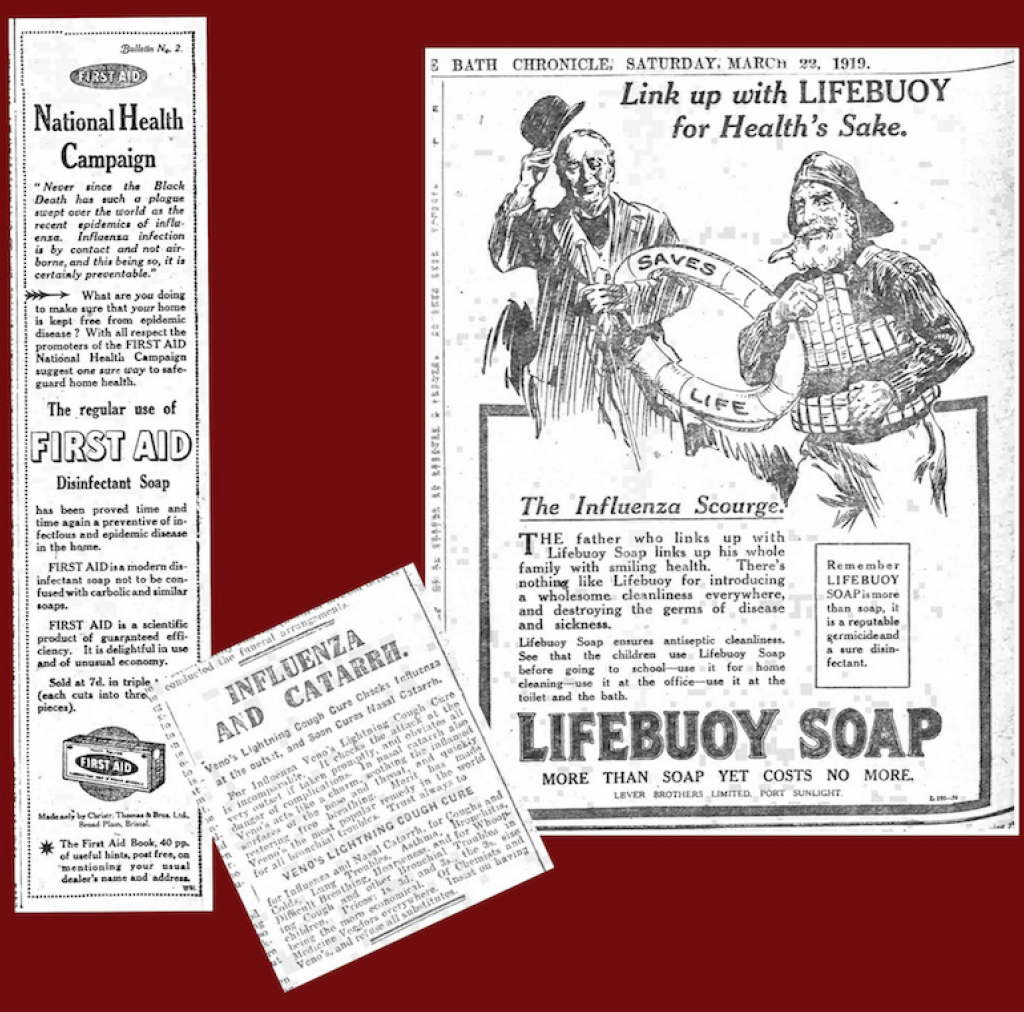

At the start of the epidemic in 1917, Britain was still at war and newspaper content was censored to prevent the enemy accessing strategically important information. Even when the war ended in 1918 there was little coverage of the epidemic in the Bath newspapers: a few death notices of worthy people, advertisements for worthless quack remedies, and advice on keeping warm, getting enough sleep and eating nourishing food. The MOH’s reports were perfunctory and in no way alarmist. During the height of the epidemic in October and November 1918, the MOH for Bath reported 121 deaths from influenza and 26 from pneumonia. Almost half of the deaths were in those aged 15 to 35. Men and women were affected in equal numbers. Only 9 children died although 2692 children caught the disease. Elementary (primary) schools were closed between 8 October and 11 November and other schools reopened a week later.

The only reference to influenza in the Bath Medical Committee’s minute book for that period was an entry that the Secretary was unable to attend a BMA conference in London “owing to the stress of work during the influenza epidemic.”

According to the figures in the Bath Chronicle, plenty of people were still visiting the city. Either Bath got off fairly lightly compared with other places or the city was keen to convey reassurance to the outside world lest the many visitors coming to take the waters stayed at home, something the Bath authorities had been guilty of during the cholera pandemic in 1833 when they under reported the number of cases to central government.

A report published in the BMJ in November 1918 was critical of how the epidemic had been handled nationally. The government had been slow to give advice and investigate the cause. There was no national strategy in the early months and decisions on management were left to local Medical Officers who had their own ideas on how to control the contagion. There was a shortage of doctors caused by the war. Those working on health boards were transferred to frontline clinical work.

According to the figures in the Bath Chronicle, plenty of people were still visiting the city. Either Bath got off fairly lightly compared with other places or the city was keen to convey reassurance to the outside world lest the many visitors coming to take the waters stayed at home, something the Bath authorities had been guilty of during the cholera pandemic in 1833 when they under reported the number of cases to central government.

A report published in the BMJ in November 1918 was critical of how the epidemic had been handled nationally. The government had been slow to give advice and investigate the cause. There was no national strategy in the early months and decisions on management were left to local Medical Officers who had their own ideas on how to control the contagion. There was a shortage of doctors caused by the war. Those working on health boards were transferred to frontline clinical work.

Some lessons can be learnt from these past epidemics. The basic rule worked out centuries ago about the need to segregate people is still the most effective way of controlling the spread of contagious disease. This was often unheeded during past epidemics, particularly during the Spanish flu. The public were not always given reliable information and there was a profusion of quackery and other useless advice. Case and mortality rates were sometimes manipulated to maintain local economies.

History can remind us that new virus diseases periodically cause death and disruption to human societies. In the relatively epidemic-free progress of the twentieth century we may have forgotten that.

Article by Dr. Roger Rolls.