2019 was a seminal year in the long life of the Bath Mineral Water Hospital. After 277 years of continuous clinical activity, its services were finally transferred to a new unit at the Royal United Hospital in Bath. The old eighteenth-century building in Upper Borough Walls, designed by John Wood, was sold and will be transformed by its Singaporean owners into a luxury hotel.

Known originally as the General Hospital, it was renamed in recognition of its use of the Bath spa waters as the basis of all its treatments. It acquired its final name ‘The Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases’ in 1935 to better reflect the fact that the hospital had developed into a specialist treatment centre for rheumatic disorders. In Bath, the hospital is still referred to affectionately as ‘The Min’.

The hospital had a close association with the Hoare family whose Wiltshire seat was at Stourhead, a magnificent Palladian mansion and grounds now belonging to the National Trust. Sir Richard Hoare (1648-1718) founded Hoares Bank in 1672 and his second son Henry (1677-1725) became a partner in his father’s bank. He was the builder of Stourhead House and was known as ‘Good Henry’ on account of his philanthropic work.

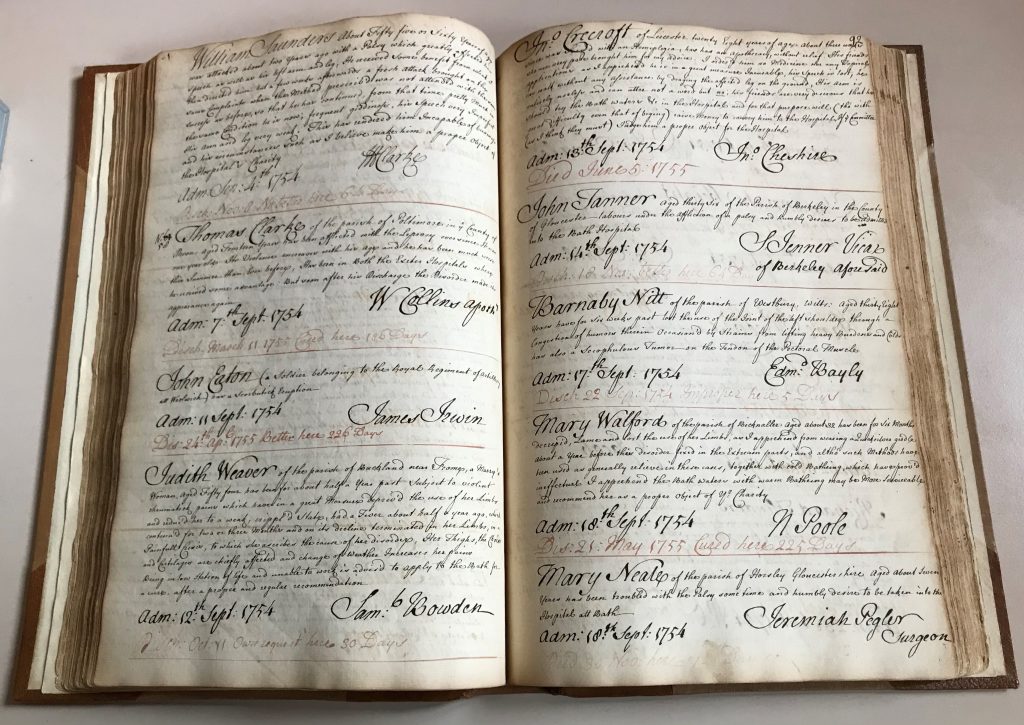

‘Good Henry’, and his wealthy philanthropist friend and customer, Lady Elizabeth Hastings, were credited by John Wood with making the original proposal in 1716 to establish a hospital in Bath using the renowned spa waters as the treatment. Central to the rationale of the hospital was the eradication of vagrancy in Bath. It was not to be an amenity for local people or for the rich and fashionable who flocked to Bath for a cure and a good time, since they were able to avail themselves of the spa waters without requiring either accommodation or financial assistance. The principle of the new hospital was the provision of Bath water cures to the ‘well recommended’ poor and needy from all over the country, providing accommodation and treatment for as long as necessary. At the same time, it was to be hoped that the ‘undeserving’ vagrants and beggars from elsewhere, who were naturally attracted to the rich pickings in Bath, would be expelled by the magistrates.

It was to be an entirely charitable enterprise, based on voluntary subscriptions and donations and no doubt modelled on the recently established Westminster Hospital which was to a large extent Henry’s brainchild. His choice of Bath for another voluntary hospital was not surprising. His father Sir Richard had embraced the Bath water cure for his ailments and supplemented his visits to the city with orders for its bottled water. In 1701 he wrote to a local tradesman Mr Long;

Good Henry was a long-term campaigner for charity education in London. His close friend and fellow activist Robert Nelson founded a charity for a Blue Coat School in Bath in 1711 but died three years later and thus it was Henry who laid the foundation stone of Nelson’s school in Sawclose in 1722. In much the same unhappy way Good Henry himself did not live to see his hospital in Bath built. Master of the Rolls Sir Joseph Jekyll, an arch do-gooder and sponsor of the Gin Act (introduced to tax the spirit out of the reach of the poor) managed to raise some funds by 1723 but no satisfactory site could be found for building a hospital.

A committee of thirteen, with a strong representation of doctors, was convened to run the charity and administer ‘outdoor relief’ in the absence of a building. The original scheme was not dead, however, and two unrelated events brought it to fruition. The first was the arrival in Bath from London in 1727 of the talented young architect John Wood whose patron the Duke of Chandos, a Bath landowner, employed Wood to rebuild St John’s Hospital in Bath which he did using local stone and in the Palladian style. The second was an Act of Parliament passed in 1737 which obliged all playhouses to be licensed. This caused many provincial playhouses to close, including the Bath Playhouse in Upper Borough Walls. Interestingly, the same Joseph Jekyll had introduced this legislation largely to put a stop to the performance of satirical plays which made fun of politicians. The Bath playhouse site was ideal for a hospital, being just inside the old city wall with an open-air outlook over the fields of Lansdowne. The trustees of the charity bought the site, demolished the theatre, paid off the neighbours whose land they wanted and instructed John Wood to design their hospital in the new fashion. The result was the building which is still standing on the corner of Union Street and Upper Borough Walls. Ralph Allen, the proprietor of Prior Park ‘a noble seat which sees all Bath and … was built, probably, for all Bath to see’ chose also to be seen for his patronage of the new hospital and donated all the stone from his quarry at Combe Down and £1000. Allen was rewarded by being made President of the Hospital in 1742.

Bankers to the Hospital

Benjamin and his nephew, Henry Hoare II, were appointed bankers to the hospital from its inception, a relationship which only ended in 1950 after the formation of the National Health Service. The trustees had raised sufficient funds by 1737 to start building the hospital, but they realised that publicity would be key to its success. In this respect, they were helped by one of the bankers’ customers, Beau Nash, who as ‘Master of Ceremonies’ was highly influential in the city.

John Wood published a broadside in 1738 showing an elevation drawing and ground plan for the hospital as well as describing its purpose and arrangements in full detail. Nash ensured that the message was broadcast nationally by putting advertisements in the national newspapers. The hospital’s weekly committee instructed Benjamin Hoare to publish a list of subscriptions received by the bank every month in the London Gazette. Nash’s powers of persuasion were legendary as was his influence over the social life of the city. He made certain that the well-heeled visitors to Bath had their pockets tapped for contributions to the new hospital at every social occasion they attended. Players at his gaming tables could not avoid him, and neither could the congregation at the biannual charity sermons at Bath Abbey, where Nash would be seen with his charity plate. Governors of the hospital were men of substance; a minimum donation of £40 was required to qualify for appointment. There was no limit to the numbers but the position did not carry with it any rights of presentation and thus there could be no suspicion of furthering private interests among the governing body.

Many were not from Bath, or its vicinity, such as Good Henry’s son ‘Henry the Magnificent’ (1705-1785), and his friend the philanthropist Robert Dingley, whose daughter Susanna married Benjamin Hoare’s son Richard, and they did not attend the weekly committees which ran the hospital. The office of President was reserved for exceptional benefactors and those whose names would add lustre to the institution. In 1776, the year of the outbreak of war with America and after 35 years of service as governor and banker to the charity, Henry the Magnificent was elected President of the Mineral Water Hospital. In late January 1747 his younger brother, Sir Richard Hoare Kt, (1709-1754) arrived in Bath with his wife Elizabeth. He had recently completed his year in office as Lord Mayor of London during which time the security of the country had been threatened by the Jacobite Rebellion. To alleviate the suffering of the soldiers who had taken part in suppressing the rebellion Sir Richard established a fund known as the Guildhall Subscription with a hefty personal donation of £3,352 7s 8d. The money was distributed almost immediately. The major beneficiaries were three hospitals, each of which received £1000; St Bartholomew’s and St Thomas’s in London and the ‘General Hospital in Bath’. This was paid on 13th February, two weeks after Sir Richard arrived in the city and represented more than twice the balance currently held in the hospital accounts.

Repeat Prescriptions

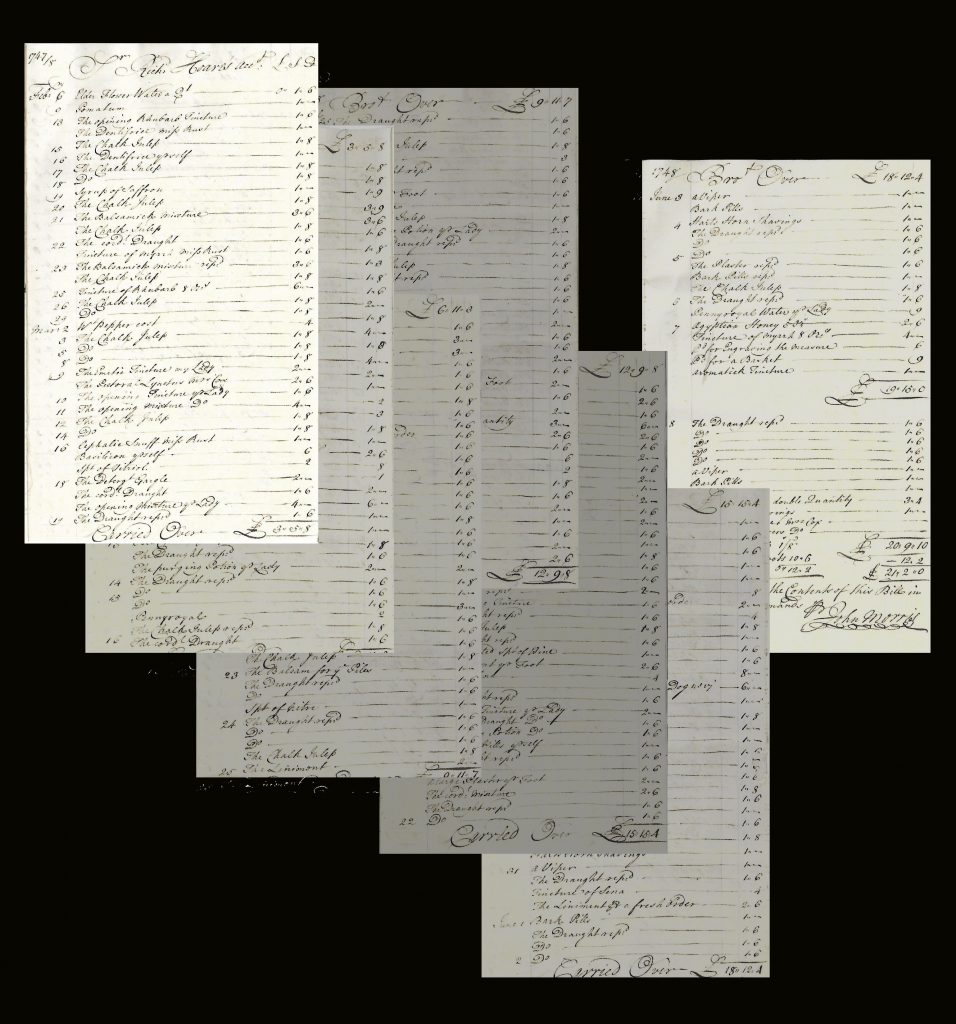

We have a good idea of the cost of Sir Richard and Lady Hoare’s daily life in Bath since they carefully preserved all their household bills for the four-month period of their stay. These included a lengthy itemised invoice from John Morris, the first apothecary appointed at the Mineral Water Hospital. Apothecaries at the hospital were paid a salary, unlike the physicians and surgeons who held honorary posts. All of them however benefited from their hospital posts. The authority which the hospital gave to the spa waters as a serious treatment enhanced the individual reputations of the medical practitioners associated with it, which was greatly to the advantage of their private practices. Scarcely a day passed from 6th February until their departure for London on 10th June without a remedy or medicine being dispensed by Morris for the Hoare household. Most were repeat prescriptions for all manner of digestive disorders: ‘purging potions’, ‘the chalk julep’, ‘the balsamick mixture’ or ‘tincture of rhubarb’, others were for nervous complaints ‘the nervous pills, a box for Lady Hoare’, or fevers ‘febrifuge pills’, emetics were prescribed for gout and various ‘plaisters’ and poultices for joint pain and swellings.

Dr Oliver, senior physician at the hospital, was a strong believer in administering purgatives and emetics to the patients in order to make the water treatments more effective. Hartshorn shavings were prescribed to be boiled and made into a nourishing jelly. Juniper berries were thought to be detoxifying, pennyroyal was used as an antidote to hysteria and chamomile was administered as an anti-inflammatory.

The Hoares travelled with their own glass and china (including an armorial tea set) and silver but spent freely in Bath. The bill from Evan Thomas the wine merchant for port from 5th February – 1st June, during which time 17 dozen bottles and two gallons were consumed, was £20, only a pound less than the medical bill from John Morris. Beer for the period cost £9 for 18 kilderkins (18-gallon casks) and brandy was 6s a bottle. The other major expenses beyond food, coal, servants and tailoring bills were their lodgings which amounted to £45 10s for 19 weeks and full livery for their coach horses for which they were charged £17 0s 7d for 126 nights. Sedan chair hire to ferry them around Bath cost 11 guineas for 11 weeks in addition to the cost of hiring horses for ‘an airing’ at 5s for a pair per day.

Henry the Magnificent appears to have followed a similar medical regime that was prescribed by John Morris for his brother Richard. Writing to his son in law Lord Bruce in 1765 he revealed that 5 grains of rhubarb and 25 grains of testacia powder ‘taken when I go to bed 3 times a week has done me incredibly good … I have persevered in it for 7 years’. He hoped it might be recommended for his daughter Lady Bruce who was a regular visitor to Bath for the water cure during the 1760s and 1770s; her health had been much undermined by a succession of pregnancies and miscarriages. Although reported as ‘parading about Bath in good health’ in 1776, she died aged 51 in 1783.

Not surprisingly Bath became the final resting place for many regular visitors who, when seriously ill, continued to seek the water cure and the services of the city’s growing number of medical practitioners as their only hope. The founder of the bank’s eldest son Richard died in Bath in 1720 aged 37. Lady Bruce’s first cousin and contemporary, Sir Richard Hoare of Barn Elms, felt revived by his visit to Bath during the Spring season in April 1786. He wrote to his brother Hugh;

On 4th October 1787, Sir Richard and Lady Hoare returned to Bath and their arrival was announced in the Bath Chronicle. This time the waters could do nothing for him and the Morning Herald was first with the news on 15th October that Sir Richard had died at his lodgings exactly a week after his arrival.

William Hoare the Artist

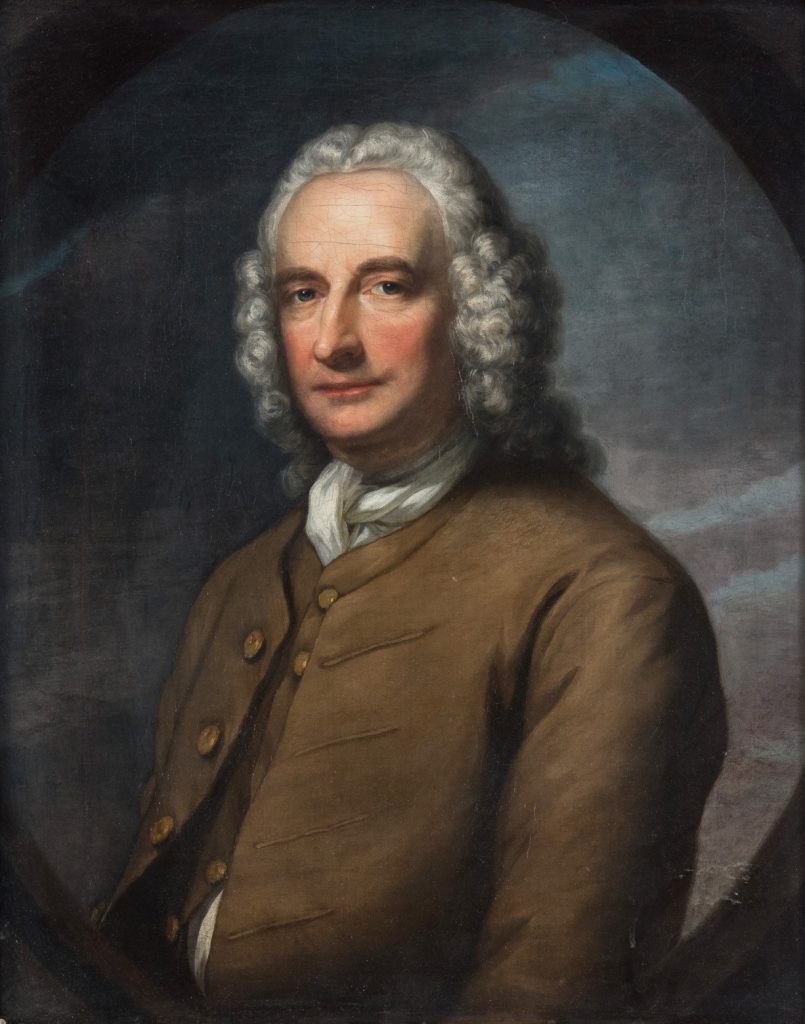

Daily life in the hospital was closely supervised by ‘House Visitors’, drawn from the governing body, who reported to the weekly committees. Prominent among them was the artist William Hoare (c.1707-1792), not a member of the banking family, but closely related to it through the marriage of his artist daughter Mary in 1765 to Sir Richard Hoare’s son, another Henry, nicknamed ‘Fat Harry’. William was a protégé of Ralph Allen whose ‘open door’ at Prior Park was extremely useful to the young artist establishing himself in Bath. In tandem with his career William Hoare took his overseeing duties at the hospital very seriously and his name appears almost weekly in the hospital minute books from the admission of its first patients in 1742 until 1780 when, aged 73, he was awarded the title of ‘Esquire’ rather than plain ‘Mr’. This elevation was no doubt in recognition of his exceptional service to the hospital but also in gratitude for the gift of several paintings.

By 1780 William was well established as the leading portrait painter in Bath. His sitters included some of the principal benefactors of the hospital; Beau Nash, Ralph Allen, and Sir Robert Dingley as well as those with professional connections. His gifts to the hospital included a magnificent ‘conversation piece’ depicting the first physician Dr William Oliver and the first surgeon Mr Jeremiah Peirce deliberating over the admission of three new patients which he presented to the hospital in 1762, and a portrait of the hospital treasurer, Daniel Danvers, which he gave to the hospital in 1780. Now as then the public areas of the hospital provided ideal gallery space and William would not have been unaware that some of his best pictures would be seen by the great and the good as they passed through. The artist’s friendship with Henry the Magnificent pre-dated the marriage of his daughter into the family and was founded on a shared love and knowledge of the arts. William was a regular visitor to Stourhead and on Henry’s instruction painted portraits of the family and views of his new pleasure garden. A set of pastel portraits of the family of Sir Richard Hoare of Barn Elms, half-brother of ‘Fat Harry’, attributed to William Hoare and his daughter Mary can be seen in the Little Dining Room at Stourhead.

Financial and Therapeutic Success

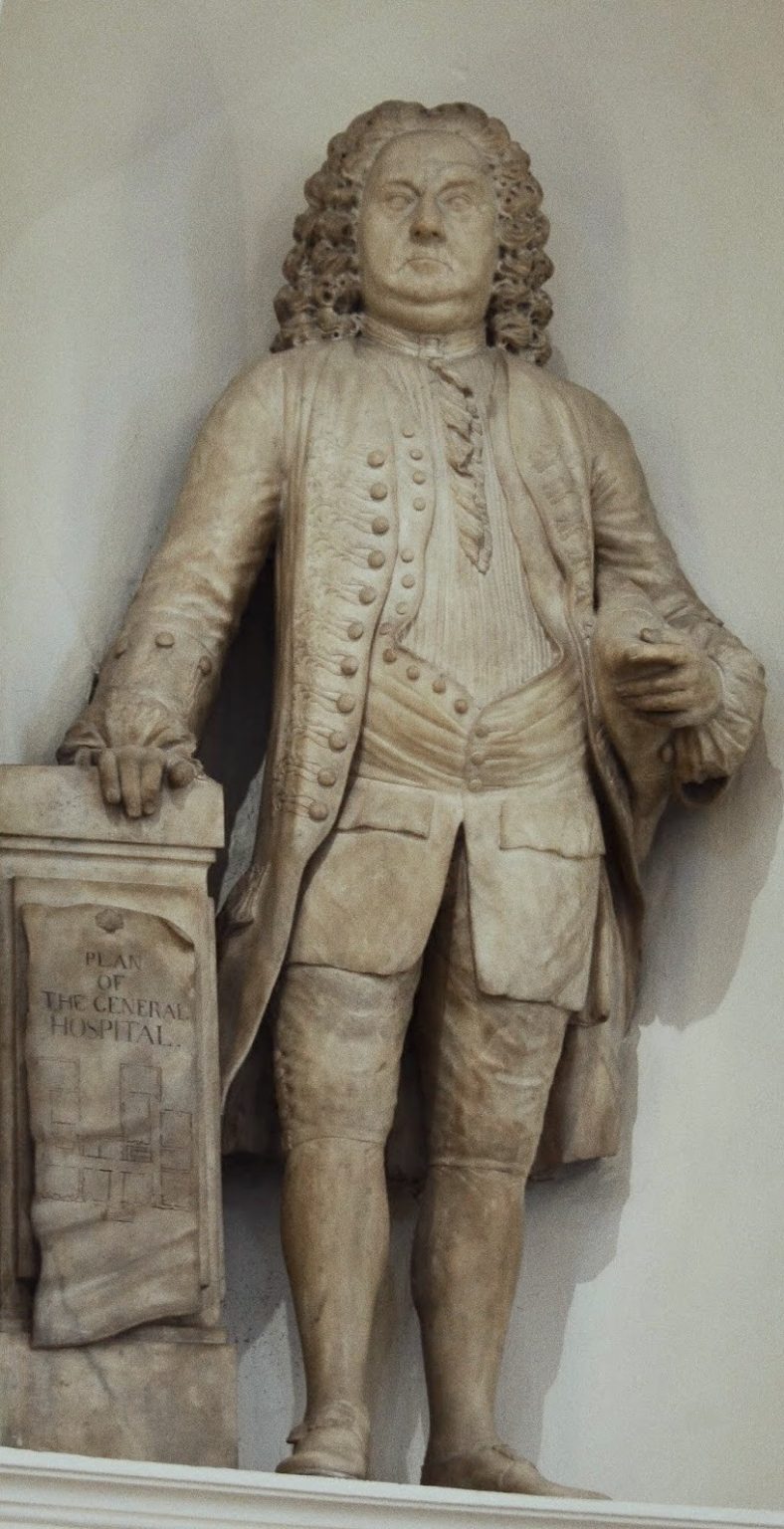

On 14th March 1738, Benjamin Hoare wrote to Francis Fauquier, who became the first treasurer of the new hospital, advising the trustees on how to attract subscribers. While supporting the publication of donors’ names and contributions, he cautioned them to include every small sum in order not to offend those giving modest amounts but also to delay any publication ‘until the King was applied to and his benefaction received’. The Royal family led by George II contributed £700 to the hospital prior to its opening for patients in 1742. Giving to the charity was undeniably associated with social prestige and the fact that its remit was national, not local, added to its success in attracting funds. Beau Nash, whose commemorative statue in the Pump Room depicts him carrying a plan of the Hospital in his hand, was critical to the promotion of the charity in London. It also undoubtedly attracted philanthropic interest from the health tourists and pleasure seekers who flocked to Bath for treatments and the ‘season’. Bath retained its pre-eminence as the most fashionable resort in the country throughout the eighteenth century.

Mortality rates at Bath General Hospital were low. Less than five per cent of patients died in hospital. Patients were classified on their discharge by categories; the greatest number were described as cured or much better; fewer than ten per cent were pronounced incurable. Statistics relating to the condition of patients at discharge were published in the local newspapers. The governors were anxious to make it known that cure, in many cases, meant relief as many of their inmates were sent to them with ‘leprosies, palsies, old inveterate rheumatisms or lameness, contracted many years ago’ and had often been discharged from other hospitals as incurable. The hospital thus maintained its reputation as a place where treatment was on the whole successful.

The Hoare family were patrons of Bath in the broadest sense. They were, like thousands of others, consumers of the spa water therapies and medical services as well as the sophisticated social offerings which made the place such a desirable retreat. Good Henry’s dream for a voluntary hospital in Bath became a reality with the support and expertise of his banking successors. The relationship between the bank and the hospital lasted for over 200 years during which time the hospital more than doubled in size. The original John Wood building became the east wing of an extended hospital but was left unaltered in its external appearance, apart from the addition of the third storey in 1793. Despite the much-altered appearance of its surroundings, the original General Hospital in Bath would be instantly recognisable today to all those who visited or worked there 250 years ago not just as a building but as a hospital which continued to play a vital role in the health of the nation.

Article by Victoria Hutchings.

Images by kind permission of the archives of C. Hoare & Co., the National Trust, the RNHRD Collection, the Royal United Hospitals Bath, the Getty’s Open Content Program, the Bath Record Office, and Bath & North East Somerset Council.

C. Hoare & Co. is the United Kingdom’s oldest privately owned bank. At the core of their business are the values of honesty and care, which have been passed on through the continued direct ownership of the Hoare family since the bank was founded by Richard Hoare in 1672 at the sign of the Golden Bottle on London’s Cheapside, before moving to Fleet Street.

The Golden Bottle Trust was established by the partners of the bank in 1985. Since then, it has supported the philanthropic commitments and principles of the Hoare family. Bath Medical Museum are enormously grateful to the Hoare family and the Golden Bottle Trust for their generous donation of funds and ongoing support of the museum’s mission.

Further information on the Golden Bottle Trust and C. Hoare & Co. can be found via their website at www.hoaresbank.co.uk.