Bath Medical Museum has recently negotiated the use of the Old Hetling Pump Room. The building, which is opposite the Thermae Bath Spa centre, has been used as the ‘Spa Visitor Centre’ since the modern spa opened just after the turn of the new Millennium. It provides information about the spa’s historic development and so coincides with the aims of the BMM to disseminate an understanding the city’s medical heritage. The museum plans to mount a series of temporary exhibitions and events for the public to enjoy.

The Hetling Pump Room is always open on Mondays from 12pm to 4pm for curatorial activities and to view small exhibitions. We are also open on Tuesdays for The Wellbeing Group which meets from 2pm to 4pm. In addition, the opening hours extend when BMM is open for major exhibitions. The opening hours are advertised in advance along with details of the exhibitions.

A ‘Small, Neat, and Convenient Room’: the History of the Hetling Pump Room

The Hetling Room is opposite the Thermae Bath Spa and close to the Cross Bath. It has a fascinating history, relatively hidden in the annals of the city, yet it is a history that is integral to the story of ‘the waters of Bath.’

The complex of buildings on the south aspect of Hetling Court, between Westgate Buildings and Beau St, incorporate the Abbey Church House (previously 2 Hetling Court), Tudor in origin, but likely to have replaced medieval buildings. There is conjecture that there was a leper hospital in the medieval period, but that is not proven, and it is questionable that a leper hospital would have been located within the crowded city – though there are indications that a leper bath existed. It is likely that the Abbey Church House was the home of the Prior or ‘Master’ of St John’s Hospital – the Hospital on the north side of Hetling Court, dates to the 12th century and in the Tudor period would have continued to offer support for poor and sick people and to be a refuge for travellers. The historian Elisabeth Holland has painstakingly examined the relevant detailed records to assess the early history of these buildings (Holland, 1998).

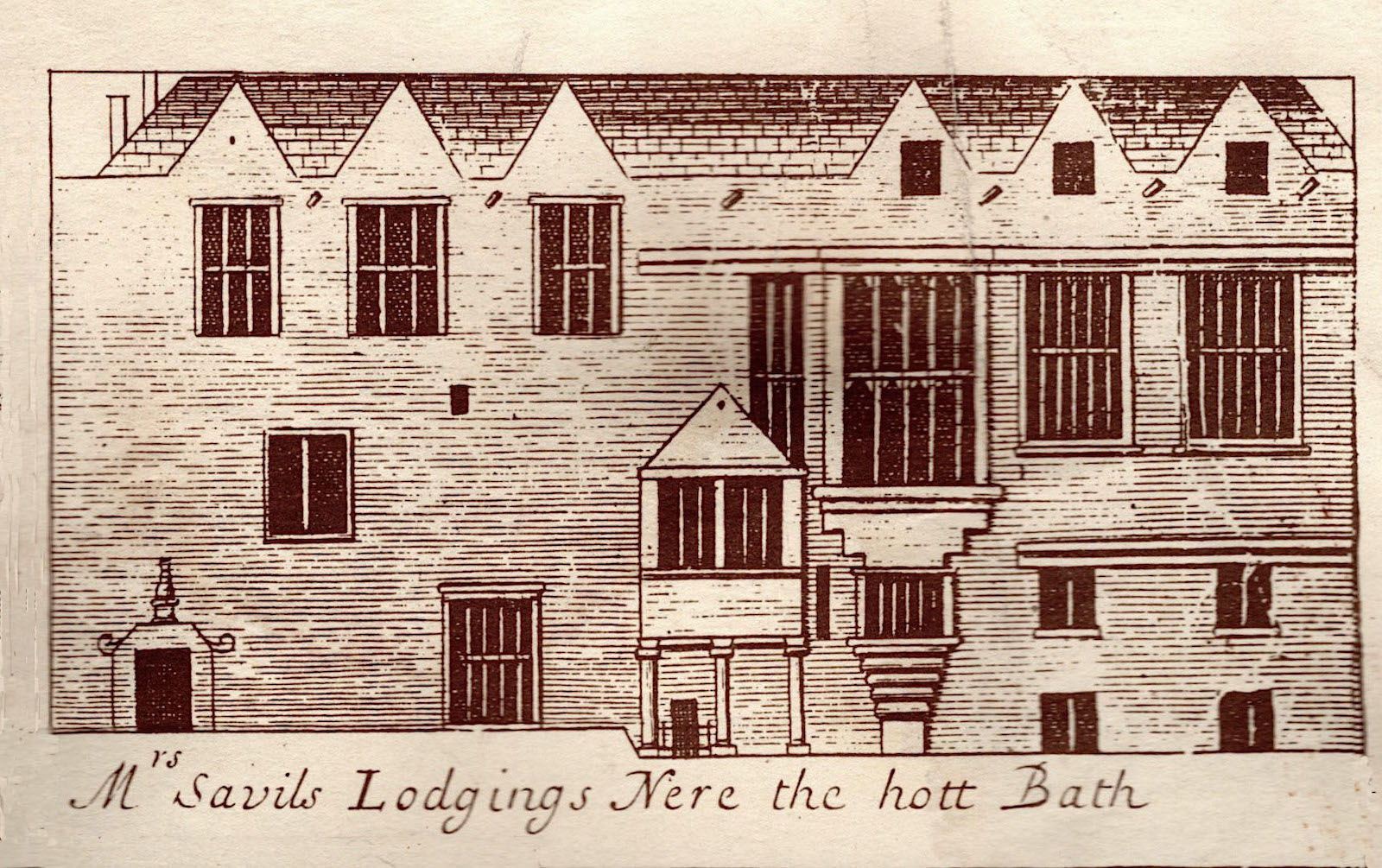

It is reputed that when the house was owned by the Hungerford family, the King’s troops were stationed there in the 1640s, during the English Civil War. The Abbey Church House was extended, and records show that the Hot Bath, still in its medieval location, was popular – it was adjacent to what is now the Hetling Room. The house was further developed in 1717 by a wealthy apothecary, William Skrine- he had married Mrs Savil who ran part of the house as lodgings ‘near the hott bath’. The prominent Bath architect, John Wood the Elder, reported that bathing in the thermal waters was provided in the building (Source -The Gainsborough Bath Spa hotel website). In 1740, Princess Mary of Hesse, fourth daughter of George II, lived there and it was described as ‘the second-best house in the city’ (Source – Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald, 1940).

Who were the Hetlings?

By the mid-18th century, the Hetlings had arrived in the city. Ernest Hetling (previously Ernst von Hetling) was a successful wine merchant, a Hanoverian associated with King George II. His son was William Hetling who was said to have been a surgeon. The Hetling family settled in the old Hungerford House (now the Abbey Church House) and changed its name to Hetling House (Le Faye, 1997). It can be surmised that their connection with Princess Mary had led them to their new home. The adjacent building became a pump room, opened circa 1770, where people gathered to drink the waters, rather than to bathe. The pump room was fed from the same thermal spring source which also supplied a bath in the Royal United Hospital (now the Gainsborough Spa Hotel) – that source was the Hetling Spring. John Wood the Younger relocated the Hot Bath in the 1770s to allow for more extensive use, reflecting the fact that the Hetling Spring was in fact one of the three main mineral water springs that rose in Bath.

The Austen Connection

Significant economic turbulence associated with the Napoleonic wars disrupted planning and building improvement in Bath in the late 18th century, but in 1804 John Palmer’s design for the Hetling Pump Room was completed. He was the city architect, and his contemporary, classical architectural style was reflected in the four-column Tuscan portico over the entrance (Hembry,1990).

This lesser, quieter pump room was favoured by many visitors including Edward Austen who suffered from ill health (Sullivan 2011). Jane Austen accompanied him on a visit to Bath to take the waters. Their father, Reverend George Austen, retired to live in Bath and died in the city in 1805. Edward was said to have complained of several symptoms and conditions, including faintness and gout. In her letters, Jane Austen referred to Edward as EAK – he was Edward Austen Knight, having been adopted by the Knight family, wealthy relatives of his father, from Godmersham in Kent.

In 1815 the Bath Corporation acquired from St John’s Hospital the freehold of the house that occupied part of the site that was to become the Hetling Pump Room. A pamphlet ‘The Mineral Spa of Bath’ was circulated in the city in 1820 by the Spa complex lessees, Messrs Green and Simms, who described the Hetling Pump Room as ‘handsomely furnished and admirably suited for the invalid…the celebrated thermal springs of Bath issue from marble vases, they are dispensed to the drinkers.’

Joseph Hume Spry, a Bath physician who advocated therapeutic use of the spa waters, remarked that the waters at the Hetling pump room were not so strong as those at the Kings Pump and therefore they were helpful as preparation for progressing to the fuller strength mineral waters (Hume Spry, 1822).

Belville Penley’s initiatives

In 1850 the Bath Annual Directory listed the Hetling Pump Room superintendent as Belville Penley. The Census record for 1841 shows that he had that role then, at the age of 30, his family being resident at Hot Bath St. By 1851 his growing family had moved to Great Stanhope St. It is likely that Belville was an entertaining character, being from a travelling theatrical family who staged many comedic performances at the Bath Theatre Royal. Belville was born in Kent in 1804 and was reputed to have acted as a child in Brussels on the eve of Waterloo, afterwards visiting the battlefield with family members. He was plagued by financial difficulties and put on concerts in the Assembly Rooms featuring his wife Mary, a noted singer, especially of oratorio and religious works. Belville’s previous theatrical production initiatives at Cheltenham and Gloucester had ended in bankruptcy. A bolder initiative was his leasing of the whole of the Baths complex from Earl Manvers in 1857 (Stockwell, 2015). A favourable review was given in 1860 by James Tunstall M.D. who observed that considerable improvements had been made in these ancient baths. He also remarked that Penley had lately introduced the Mineral Waters in an effervescing form (Tunstall, 1860).

By the 1870s, the use of the Hetling Pump Room had dwindled so much that there was serious assessment of its financial viability and calls for it to be closed. Dr R. W.Falconer advocated that this smaller pump room was more desirable for those invalids who found the main Pump Room too crowded. Falconer described the Hetling Pump Room as a ‘small, neat, and convenient room, where the water was supplied to invalids by means of a pump, which draws it from the spring, which rose into a reservoir, under the adjoining street. The water was delivered from the pump at a temperature of 114 degrees Fahrenheit’ (Falconer, 1880). Falconer added that the Pump Room was unnecessarily closed in 1875 although there are references to reopening and popular use in the 1880s.

A reference dating to 1883 described how the rooms above the Pump Room accommodated ‘the pumper’, also the offices of the Yeomanry and occasional meeting space for the Bath & West Agricultural Show. In 1887 the house containing the old Hetling Pump room was secured and opened as a nurse’s institute in association with the nearby Royal United Hospital. An 1888 tourist guide states that the Hetling Pump Room was specially adapted for invalids (Worth, 1888). Belville Penley, who can be noted for his long association with the Hetling Pump Room, died in Bath in 1893.

The 20th Century Onwards

During the 20th century the Hetling Room was no longer functioning as a Pump Room. but became an interpretive centre for the Hot Bath. There was disruption and devastation affecting Hetling Court, during the WW2. In April 1942, bombing destroyed much of Abbey Church House and led to the necessary restoration of the west front. The bombing of Bath was one of the so-called Baedeker raids by the Nazi Luftwaffe, targeting sites of cultural and historical value. Over 400 people were killed.

The old Hetling Court Pump Room at 1 Hetling Court was listed in 1950 as Grade II by English Heritage (now Heritage England). The Hot Bath finally closed in 1976 when the Royal Mineral Water hospital ceased to use the facility, having built a new pool in the hospital. (Source – Great Spa Towns of Europe website). The hot mineral waters of the Hetling Spring are now one of the sources for the Thermae Bath Spa in its remarkable building completed in 2006. The Hetling Room continued as an interpretive centre, with a new lease of life in 2023 when the Thermae Bath Spa approved a licence for its use by the Bath Medical Museum. So, it is fitting that the history of the therapeutic use of the mineral waters of Bath will continue to be extolled in one of the city’s heritage pump room locations.

References

Falconer R.W. (1880). The Baths and Mineral Waters of Bath, Churchill: London.

Hembry P.M. (1990). The English Spa 1560 – 1815: A Social History. Athlone Press: London.

Holland E. (1998). Hetling Pump Room and Hetling House The Magazine of the Survey of Old Bath and its Associates. History of Bath Research Group: Bath.

Hume Spry J. (1822). A Practical Treatise on the Bath Waters, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown:

Le Faye D. (1997). Jane Austen’s Letters, OUP: Oxford

Stockwell A. (2015). What’s the Play and Where’s the Stage? A Theatrical Family of the Regency Era Vesper Hawk Publishing: London.

Sullivan M. (2011). The Jane Austen Handbook: Proper Life Skills from Regency England, Quirk Books: London.

Tunstall J. (1860). The Bath Waters: Their Uses and Effects in the Cure and Relief of Various Chronic Diseases John Churchill: London.

Worth R.N. (1888). Tourists Guide to Somersetshire: Rail and Road Stanford: London