Dispensaries provided medical care for the poor between the eighteenth and first half of the twentieth century and most cities and towns in the United Kingdom had at least one of these charities. Bath had several which provided a key part of medical care for the poor.

Like the voluntary hospitals they were supported by subscribers who paid an annual sum to their institution and, in return, received a small book of tickets of recommendation that they could hand to the sick poor who would take them to the local dispensary to obtain medical care, either in the building, or at their home. The only alternative sources of medical care at this time for the poor were the hospitals and the workhouses. The former were very crowded and reluctant to allow access to anyone likely to be suffering from an infectious disease. Workhouses were feared because of the shame and stigma associated with the name and the separation inside of men, women and children once they were admitted. The poor care that was often provided in workhouse infirmaries was another factor which contributed to their unpopularity.

In 1747 a charity was created in Bath to gratuitously serve the sick poor of the city and the surrounding neighbourhood. Known as the Pauper Scheme, some physicians and surgeons in the city gave advice and treatment to those who were ineligible for poor relief. They were able to send directions to an approved apothecary who then dispensed the prescribed medicines. After 1785, sick paupers had access to a Poor Law Dispensary and in 1790 the Pauper Scheme itself was expanded to become the Bath City Dispensary Infirmary. In 1823, the institution merged with the Bath Casualty Hospital to become the Bath United Hospital (later becoming the Royal United Hospital).

The United Hospital had insufficient resources to cater for the needs of the poorer sections of Bath society. As a result, three new dispensaries were opened. The Eastern Dispensary was founded in 1832, the Western Dispensary in 1837, and the Southern Dispensary in 1850.

The most complete set of archival material that has survived relates to the Southern Dispensary. It largely consists of Minute books and annual reports which are now stored in the Bath Records Office.

Southern Dispensary

Originally called the Lyncombe and Widcombe Dispensary, it changed its name to the Southern Dispensary in 1854. The population of this suburb increased nearly 4 times during the first half of the 19th century and possessed the highest mortality rate of all the Bath districts during the period 1838 to 1844. The institution opened on January 1, 1850. There were two surgeons and a dispenser.

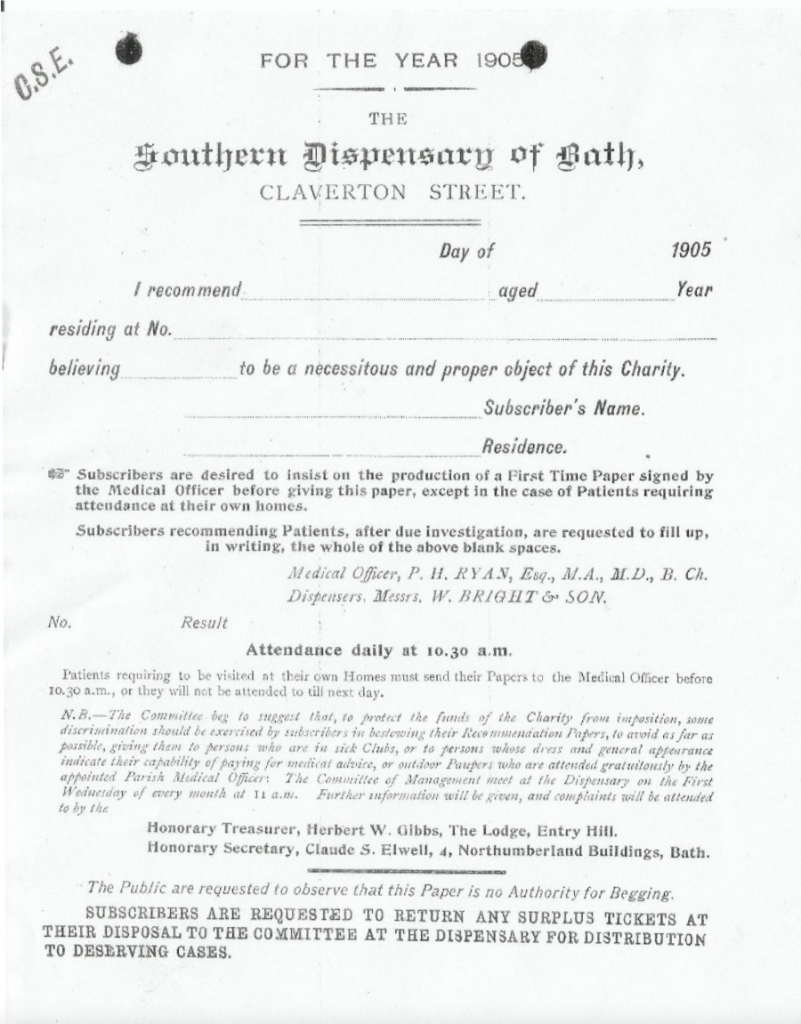

The original dispensary was in the basement of 26 Claverton St which had once been a cold bath house. The two surgeons who gave their services gratuitously, attended from 10am to 11am each day and the dispenser was paid £15 a year. He attended at the same time as the surgeons and also from 5 to 6 pm. Patients needed to get a letter of admission from one of the subscribers to the dispensary. Each subscriber was given one letter for each two shillings and sixpence subscribed. There were originally 85 subscribers of whom 11 were clergyman, 8 had a senior military rank and 51 were male.

1000 patients were seen in 1851 of which about half were visited in their homes. By 1854 the need for larger premises was pressing and a building fund was started on a piece of land donated by Earl Manvers. The foundation stone was laid in 1855 and the building opened in 1856 in Claverton Street, Widcombe. It consisted of the surgeons’ room, the dispensary, a large waiting room and a private apartment, with quarters for the housekeeper in the basement. In 1859 the two appointed surgeons resigned and the committee had no applications for replacements. It was decided to employ a paid medical officer which meant the patients had to contribute one shilling for a month’s treatment (sixpence was charged for child under 14). These paying patients were issued with what were known as First Time Papers. Charging dispensary patients a fee, even though it was only a small amount, was a very unusual action and there seems to be no other dispensary in the United Kingdom which followed that practice except those in Bath.

The surgeon appointed in 1859 was a man called Owen Tucker who caused the committee a fair amount of trouble by not keeping proper records, and he was twice admonished for neglecting patients. In 1861 he asked for and was denied a rise in his salary. In 1868 he took a month’s leave without notice and failed to supply a deputy. He died in 1873, aged 40.

Patients were accepted not just from Lyncombe and Widcombe, but also Combe Down and Monkton Combe. Only once in the records is there any reference to the doctors’ transport; in 1891 the doctor requested an allowance on account of the rise in fares.

In 1864 the Patients’ Restorative Fund for convalescent care was started in order to provide patients with a nourishing diet. This effectively meant that doctors could provide “wine and such comforts in addition to medicines”. An early form of care quality control (CQC) was put in place on a monthly basis. Visiting inspectors had to attend the dispensary during surgery hours, note the arrival time of the doctor, and generally see that everything was run as it should be. Not all inspectors were very tactful. One interfered to such an extent that the exasperated doctor appealed to the committee who banned this particular individual (a clergyman) from joining in consultations and discussing cases in front of patients.

Minute book No 3 provides an idea of the furnishing in the building in the 1880s. The boardroom had a table and small clock, nine chairs, and umbrella and hatstand and Venetian blinds. There was a set of irons for the fire and a glass case for instruments. A district map hung on the wall. The patient’s room had four settles, an umbrella stand and a gas stove. The doctor’s room had a sofa and three chairs, a venetian blind, a wash stand with basin and some slop pails. The instruments provided were an ear syringe, and ear speculum and three gynaecological specula. There was also a stomach tube, a large pewter syringe, an electric battery, an inhaler, urinometer, a tongue depressor, a glycerine syringe, boxes of tape plasters and a box of bandages.

The introduction of the National Insurance Act in 1911 provided working men with access to free medical care, and unsurprisingly the number of patients attending the dispensary fell in the following year. Patient numbers continued to fall during the last few decades of the dispensary’s life. A mere 416 patients were treated in 1930. In 1949 the dispensary closed and became the headquarters of the Bath Central Girls’ Club. The building was demolished in the late 1960s when Claverton Street was bypassed by what is now Rossiter Road.

Eastern Dispensary

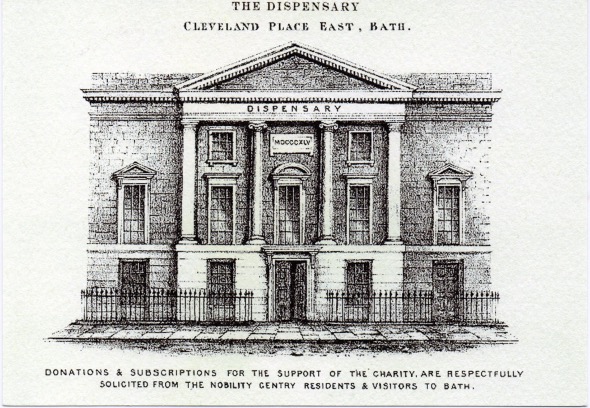

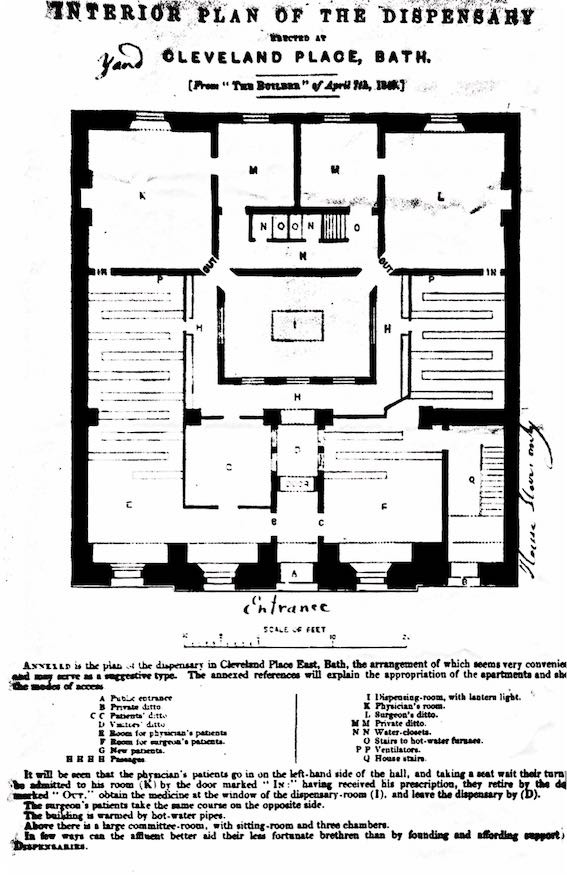

An entirely new building was erected in Cleveland Place, specifically designed to accommodate the dispensary’s activities. It was largely funded by John Ellis, a London hop merchant who retired to Bath. Ellis died in 1856 and left many legacies to dispensaries in London and Leeds as well as to the Southern and Eastern dispensaries in Bath. Like its southern counterpart, the Eastern Dispensary was originally free for patients provided they presented a ticket of recommendation obtained from a subscriber. Subscribers could purchase four tickets a year for 10 shillings or 10 tickets a year for a guinea.

The medical staff who worked in the dispensary also visited patients at home if needed. Although most of the patients lived in nearby parishes on the east side of the city, some lived further away. For example, in 1871 Dr Spender, one of the physicians at the dispensary, treated a 13-year-old girl suffering from chorea who lived at Colerne, a village 8 miles from the city.

In 1914, the first woman doctor, Effie Craig, was appointed to work in the dispensary. She was posted abroad during the war to work with the Royal Army Medical Corp.

By 1934, the number of new patients was beginning to fail off. In 1938, an orthopaedic clinic was opened in the building run by Dr. Maud Forrester-Brown, and also a gynaecological clinic. At the start of the NHS in 1948, the dispensary closed. The building has since been used for a number of commercial ventures including an art gallery.

The Western Dispensary

All trace of the dispensary premises and its records were destroyed in the second World War. The first bomb to hit the city exploded inside the building on 25th of April 1942. The dispensary was at 1 Albion Place, Upper Bristol Road, and was on the ground floor of the four-storey building. The entrance to the dispensary was by a passage between St George’s Buildings and Albion Place. A sign is still visible on the wall at the end of St Georges Buildings which reads ENTRANCE but the adjacent passageway and most of Albion Place has vanished and a modern building now stands there. Details of the dispensary’s history can be traced from reports in the local newspaper, the Bath Chronicle.

The first mention of the dispensary occurs in 1839. It was set up to benefit patients on the western side of the city including the suburb of Weston. It moved premises to Albion Place in 1857. In 1879 the annual report suggested that there were persons “well able to pay for medical attendance “who were misusing the dispensary which had been designed for the sole use of “the helpless and necessitous poor of their district”. Patients could be seen for acute illnesses if they paid sixpence for a First Time Paper but only for one consultation. More chronic problems required a Ticket of Recommendation which entitled them to ongoing care.

How did the Bath dispensaries compare with those in other British towns and cities?

Most cities and towns in the UK had dispensaries providing medical care for the poor. They were managed by subscribers and each committee of subscribers developed a dispensary that was similar to those in other towns, but they often had distinctive differences, for instance, having beds for inpatients or facilities for medical student teaching. Many committees elected patrons and chairmen who were either prominent local businessman, clergy or members of the aristocracy in order to attract new subscribers.

Initially physicians and surgeons were appointed to dispensaries, and they attended patients either in the dispensary or at the patient’s home. Gradually resident apothecaries and, later, resident medical officers lived in the dispensary and attended most of the patients there. Some dispensaries relied totally on their honorary medical staff for medical cover but most, like the Bath dispensaries, used a mixture of paid medical officers and honorary physicians and surgeons. There was also a paid dispenser attached to each dispensary who was sometimes resident. Honorary medical staff rarely received any remuneration, but by their association with the dispensary were likely to improve their local reputation in gaining increased numbers of private patients.

Each dispensary was self-sufficient and there was no association or national conferences of dispensaries. New initiatives developed within a dispensary rarely spread to other towns. The Bath dispensaries were voluntary dispensaries – they never became “provident” ones like those in many other towns and cities. Provident dispensaries adopted an insurance approach where patients paid regularly weekly or monthly subscriptions to the committee to ensure that they and their families retained free access to the dispensary. Provident dispensaries were criticised by a Bath doctor in 1855 as being “a specimen of professional impudence for the sole purpose of making money and likely to lower the status of the medical men in the eyes of the public”. All the Bath dispensaries used First Time Papers in addition to subscribers’ papers. This method requiried the patient to pay a small sum when it was felt that the problem could be cured within the space of a month. They were first used by the Eastern Dispensary in 1864. Assessing whether poor patients were able to pay for medical services was never easy and the First Time Paper initiative was popular with poor patients. It didn’t cost much and it removed the necessity of finding a subscriber and convincing them of being a worthy recipient of care.

The extraordinary system of relying on subscribers to provide a health service for the sick poor has now been totally lost. Since the advent of the NHS, impoverished people no longer have to search out subscribers to ensure that they can be treated by a doctor.

Article by Dr Michael Whitfield

For more information on dispensaries, read “The Dispensaries – Healthcare for the Poor Before the NHS.” By Michael Whitfield. Bristol. 2016. Pp. 270. ISBN 9781504997164