A young woman’s dedication

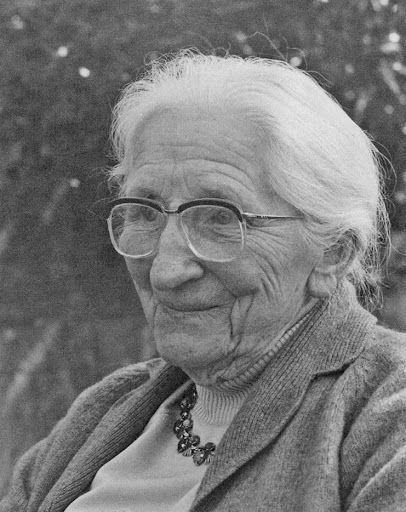

Dr Cross was born as Clara Dunbar Tingle, in Sheffield in 1900. During World War 1, Clara’s experiences as a young woman of seeing the impact of bombing strengthened her desire to become a doctor. She faced significant prejudice in applying for a medical scholarship because female doctors were very rare in the male dominated profession. The churchgoing Tingle family was effectively ostracised by their church as a response to Clara’s unacceptable ambition. Her determination was rewarded, and she qualified in the early 1920s, first being listed in the 1922 Medical Directory. Dr Tingle’s initial posts were at the Sheffield Children’s Hospital and the Jessop Hospital for Women in Sheffield. Her work as an assistant pathologist led her to focus on the relatively neglected topic of foetal and neo natal death, detailing a research study on the causes.

In 1928, Clara married Roland Cross, the founder of a manufacturing company in Bath. Their daughter Catherine was born in 1929, son Michael was born in 1937. and son Roland was born in 1940. Clara returned to work within weeks of her youngest child being born. The family lived at addresses on Midford Rd for many years. All three were to become chartered engineers.

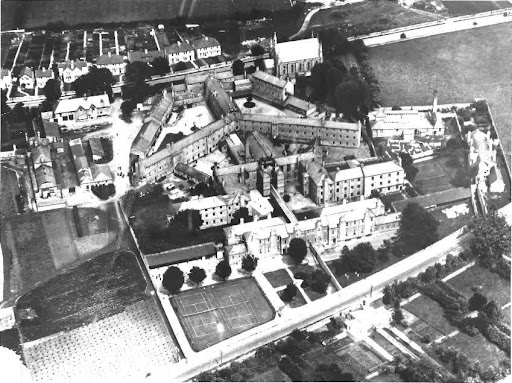

Transforming the workhouse

The Bath Union Workhouse at Odd Down had become known as St Martins Hospital after legislation that effectively upgraded many Workhouses. The buildings dated back a hundred years and included medical and surgical wards, a maternity department, a children’s ward and other buildings that were occupied by people with long term illnesses or by elderly people. In 1939 the impetus of the Second World War led the Ministry of Health to build an Emergency Medical Service (EMS) hospital in the grounds, encompassing some of the workhouse buildings. Dr Cross arrived at the hospital in 1940 to set up the emergency hospital. The conditions in the ex – workhouse wards were stated by Dr Cross to be ‘terrible,’ including reported lack of equipment, insanitary wards with leaking roofs and insufficient kitchen facilities.

The new Emergency Medical Service was intended to accommodate and treat casualties from air raids; but the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940 led to priority being given to sick and wounded soldiers returning from Dunkirk, including those patients who had experienced bombing while on board a Red Cross hospital ship. The severity of the blast injuries led Dr Cross to advocate that a blood transfusion service was needed urgently. She had specialist knowledge of blood transfusion, partly linked to her previous work in midwifery, dealing with emergencies affecting new mothers and babies.

Dr Cross contributed to understanding of the Rhesus factor, one of several blood groups which have been identified. Newly born babies who have a positive Rhesus factor known as a D antigen and babies whose mothers have no D antigen in their blood (i.e., Rhesus negative) are affected by a condition known as haemolytic disease of the newborn. The first Rhesus positive baby born to a Rhesus negative mother is unaffected, but subsequent births are progressively more badly affected and have little chance of survival. Dr Cross’s intervention with exchange blood transfusion saved the lives of 200 babies. Nowadays, the condition is completely preventable by giving Rhesus negative mothers a dose of anti-D during their pregnancies.

In 1940 the Bath Weekly Gazette reported that 675 EMS beds were occupied, rising to 757 at fullest capacity. The Royal United Hospital at Combe Park was able to transfer 80 civilian cases to St Martins to increase capacity at the RUH for injured soldiers. Treatments for injured soldiers included mineral water treatments that Dr Cross arranged at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases (‘the Min’). From 1942, Clara worked alongside Dr Fritz Kohn, the senior surgeon – he had fled from his home in Czechoslovakia due to the threat of Nazi occupation. The setting up and running of the hospital in wartime, in those conditions must have been the most exceptional challenge for a physician. The established wartime hospital had ten large wards, an x ray department, laboratory, and a dedicated kitchen.

Conditions at the hospital improved gradually – the creation of the National Health Service in 1948 led to the new EMS Hospital and the original workhouse buildings combining into a single hospital with higher standards.

‘I was a woman, and medicine was a man’s world’.

Clara’s observation above reflected her experience of marked discrimination because she was a female doctor. Colleagues from the Royal United Hospital refused to help her by providing hospital supplies. They invariably refused to address her as ‘Doctor’, instead using the term ‘Mrs’. The Bath Clinical Society excluded her from discussions concerning her own patients. Clara’s son Rodney described her as having strong moral Christian principles, a wicked sense of humour and an intolerance of pomposity – those qualities no doubt were reflected in her response to these attitudes. Her undeniable achievements later led to her being elected the first female Member of the Clinical Society and she presented a trailblazing paper on exchange transfusion.

In the post war years, Dr Cross served as a consultant pathologist, with the responsibility of reporting very frequently her analysis of the causes of death, including sudden and suspicious deaths. In her last year before retirement, she carried out 446 postmortem examinations. She also served as the area Blood Transfusion Officer and effectively introduced Bath to the benefits of blood transfusion. The area Blood Transfusion Service covered large areas of Somerset and Wiltshire, encompassing a population of 200,000 people.

Dr Cross was to carry out those roles until retirement in 1965. After retirement she was characteristically busy as a locum GP in Combe Down and Frome. The Dr Clara Dunbar Cross geriatric centre at St Martins Hospital was opened by Clara herself in November 1975. She died in 1986 but her significant contribution was also remembered in the naming of Clara Cross Lane. She should be acknowledged as being one of Bath’s most outstanding physicians, facing exceptional challenges with unwavering commitment and dedication to her patients.

References

Bath Landscape Partnership. ‘Workhouse to Hospital’, Bath Landscape Partnership website.

Chislett W.H.A. (2007). ‘Bath Union Workhouse, the Chapel, John Plass and St Martins Hospital’, in The Survey of Bath and District, No 22.

Cross C (1989) ‘In The Thick Of It’, published by Cross Manufacturing, Bath.

Tingle C. (1986). A Contribution to the Study of the Causation of Foetal Death’, in Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1986, 61, pp. 962-963.