When a person dies unexpectedly and the cause is unclear, a post mortem examination known as an autopsy may be performed by a doctor to try to ascertain the cause of death. Autopsy literally means “seeing for oneself”. As well as a careful external examination of the body, dissecting the corpse allows the interior organs to be examined so the cause of death can be more accurately established. Autopsies have been performed for many centuries although at times there have been religious proclamations banning the procedure.

The first recorded human dissection was conducted by Mondino de Luzzi in Bologna around 1315. He published Anatomia mundini which became a standard text on dissection. Internal examination was carried out in a defined order, starting with the abdomen (the cavity containing organs most likely to decompose), then the thorax and finally the cranium. This order of dissection for the three major cavities has varied over time. The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902) recommend the reverse order.

Several autopsies are mentioned in the memoirs of the Bath physician, Dr Robert Peirce (1622-1710). Unlike today they were performed in the patient’s residence and the dissection was usually done by a surgeon with the physician, and often family members, in attendance. For example, when Sir Robert Mauleverer died at Bath in 1687, his autopsy was performed the same night attended by two physicians, an apothecary and his brother. Peirce describes the appearance of the body, both externally and internally, in lurid detail. The abdomen contained a large abscess “which at first view looked the colour of an unboiled lobster; and when opened (nor did it easily yield to the knife) there spouted out at first some quarts (two or three we judged) of wheaty foetid matter which was followed by a cheesy curd”. Another of his patients, Sir Robert Craven, was dissected on the night of his death and Peirce remarked that “it was the fattest corps I ever yet saw open’d; cutting near an inch thick in fat, all down the breast and belly: all the intrals [entrails] prodigiously fat”.

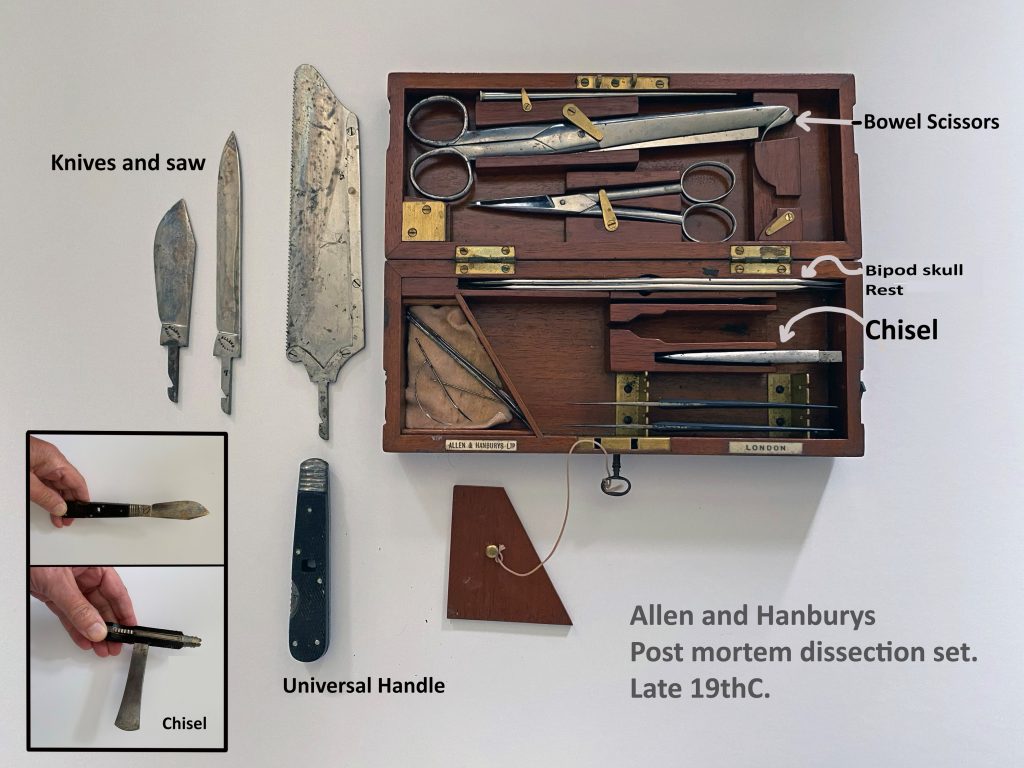

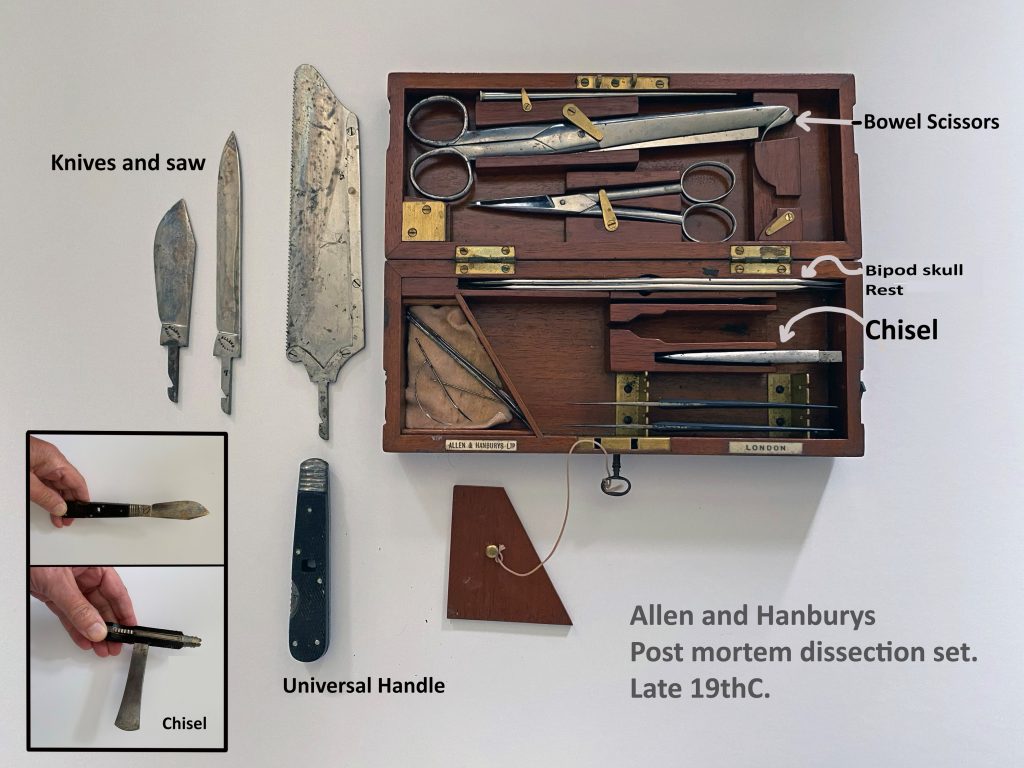

Until the 20th century, most autopsies were carried out by GPs either at a patient’s home or in a morgue, although there are accounts of post mortem exams and inquests taking place in the outhouses of inns. One Bath GP, John Cottle Spender (1801-1865) had a dissecting room in his garden at 36 Gay Street. Doctors used portable sets of instruments contained in wooden cases.

Patient’s dying in hospital were carried to the “dead room”, later known as the mortuary, where autopsies were carried out. In the 18th and 19th centuries, some hospitals established pathological museums where organs exhibiting the effects of disease were mounted in glass jars. The Royal United Hospital had such a museum but it did not survive the move from the original building in Beau Street to its present site at Combe Park. In the latter part of the last century, specimens could only be retained with express permission of the patient’s family and only a few historic pathological museums remain, mostly in long established medical teaching hospitals.

Until the 20th century, most autopsies were carried out by GPs either at a patient’s home or in a morgue, although there are accounts of post mortem exams and inquests taking place in the outhouses of inns. One Bath GP, John Cottle Spender (1801-1865) had a dissecting room in his garden at 36 Gay Street. Doctors used portable sets of instruments contained in wooden cases.

Patient’s dying in hospital were carried to the “dead room”, later known as the mortuary, where autopsies were carried out. In the 18th and 19th centuries, some hospitals established pathological museums where organs exhibiting the effects of disease were mounted in glass jars. The Royal United Hospital had such a museum but it did not survive the move from the original building in Beau Street to its present site at Combe Park. In the latter part of the last century, specimens could only be retained with express permission of the patient’s family and only a few historic pathological museums remain, mostly in long established medical teaching hospitals.

Although most post-mortem examinations required agreement of family members before they were performed, if a death was unexpected or occurred in suspicious circumstances, a coroner had the legal right to order an autopsy. All coroners are now lawyers but many of Bath’s coroners in past centuries were medically qualified and may have even performed autopsies themselves although they more usually requested the dissection to be done by a GP or surgeon.

Nowadays, autopsies are carried out by hospital pathologists or, in suspected criminal cases, by doctors specialising in forensic pathology. Forensic pathologists work between mortuaries, hospitals, the courts, and crime scenes and cover a large area of the country. Since 1944 they have to be registered by the Home Office and must have appropriate qualifications and experience, although a very small number also have medical qualifications. Communication is coordinated through the coroner’s officer, until recently a member of the local constabulary but being a police officer is no longer a mandatory requirement for this post.

Article by Dr Roger Rolls