Over the course of history thousands of ailing people visited Bath to immerse themselves in the hot waters. They came to be douched and sprayed or inhale its vapour, or simply to savour what Charles Dickens described as ‘the taste of warm flat irons’. They expected to be relieved of their illnesses by absorbing some curative property released as the waters emerged from a subterranean world of mysterious brimstone fire. They were more likely to have been relieved of their money by the city’s medical fraternity who waited upon them. When Sir Richard Steele visited Bath in 1709, he commented “The doctors here are very numerous but very charitable. I own I was cured of more diseases in one week than I had had in the rest of my life.”

The tradition of Bath’s healing waters began in the mists of antiquity. The legendary founding of Bath is ascribed to a British prince called Bladud who was cast from the royal court when he caught leprosy. Banished to the west country, he took a job as a swine herd and it was while he was tending his pigs that he came upon the steaming springs in the valley of the river Avon. Bladud noticed that when the pigs wallowed in the hot muddy pools, the blemishes and sores on their skin were miraculously healed. He took a dip himself which apparently cured his leprosy. He vowed to found a city on the site of his good fortune.

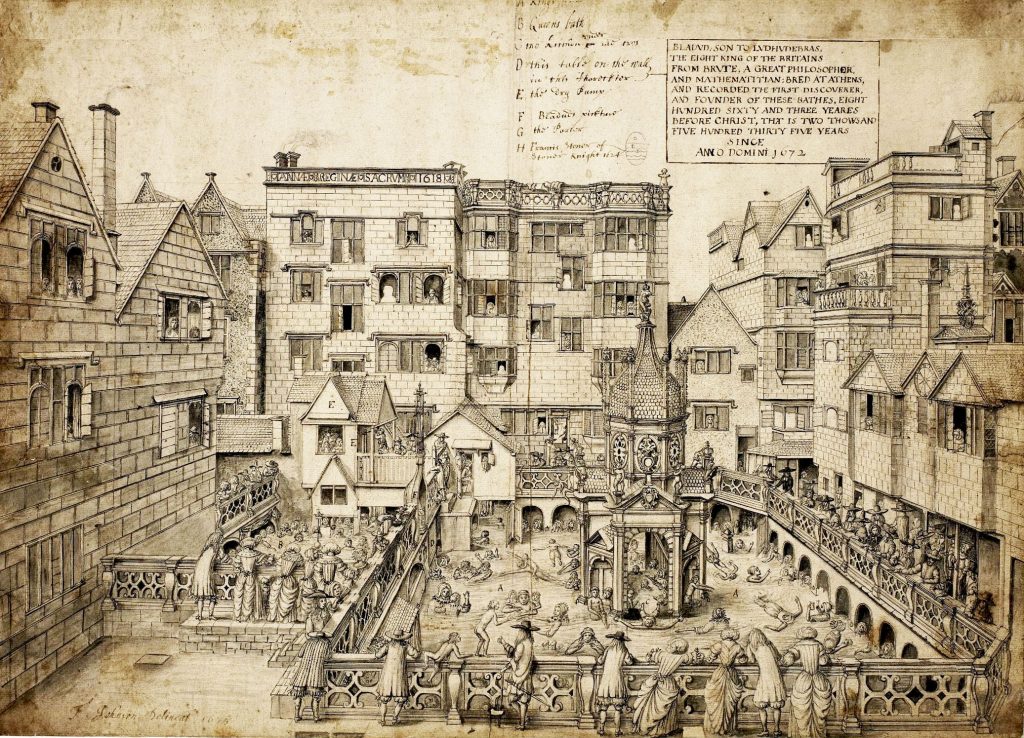

Our concept of spas originated with the Romans. Started around 50 A.D., the Roman baths at Bath attained their peak in the 3rd Century A.D. Although some Roman doctors recommended bathing to treat a number of disorders, the baths were used mainly for leisure and hygiene purposes. There is very little documentary evidence for the water’s use until the 16th century although the author of the 12th century text Gesta Stephani, which chronicles the acts of King Stephen, relates how diseased people from all over England came to wash away their infirmities in the healing waters.

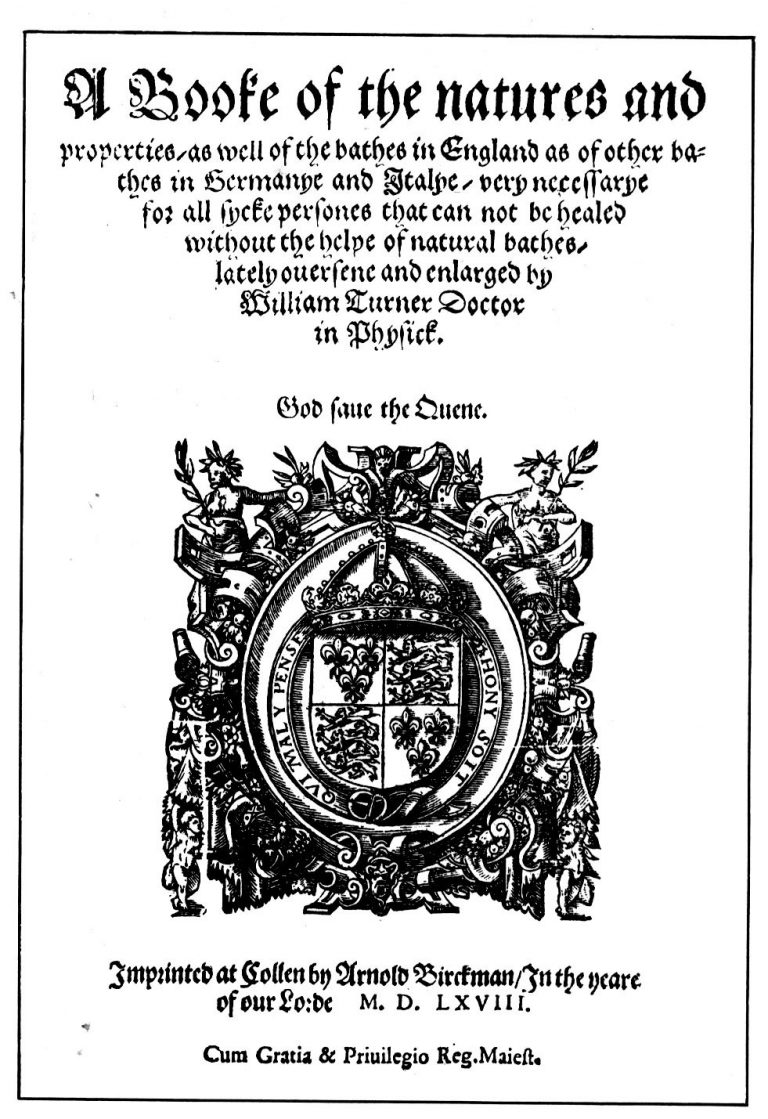

Awareness of the baths’ healing potential was re-awakened by the publication of two books on therapeutic bathing by Dr William Turner and Dr John Jones. In his publication, The Book of the Natures and Properties of the Baths of England, printed in 1562, Turner lists over sixty disorders which could benefit from bathing. These include such diverse conditions as miscarriage, piles, migraine, sciatica, worms in the belly, forgetfulness, dullness of smelling, palsy, cramp in the neck and failure of menstruation, to name but a few. In modern terms, there seems very little to link these conditions together but physicians in those days thought diseases were caused by an imbalance of the four humours: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. Most of the diseases in Turner’s list were considered to be due to an excess of phlegm, the cold moist humour, and could be cured by heating and drying the patient’s body using hot mineralised water.

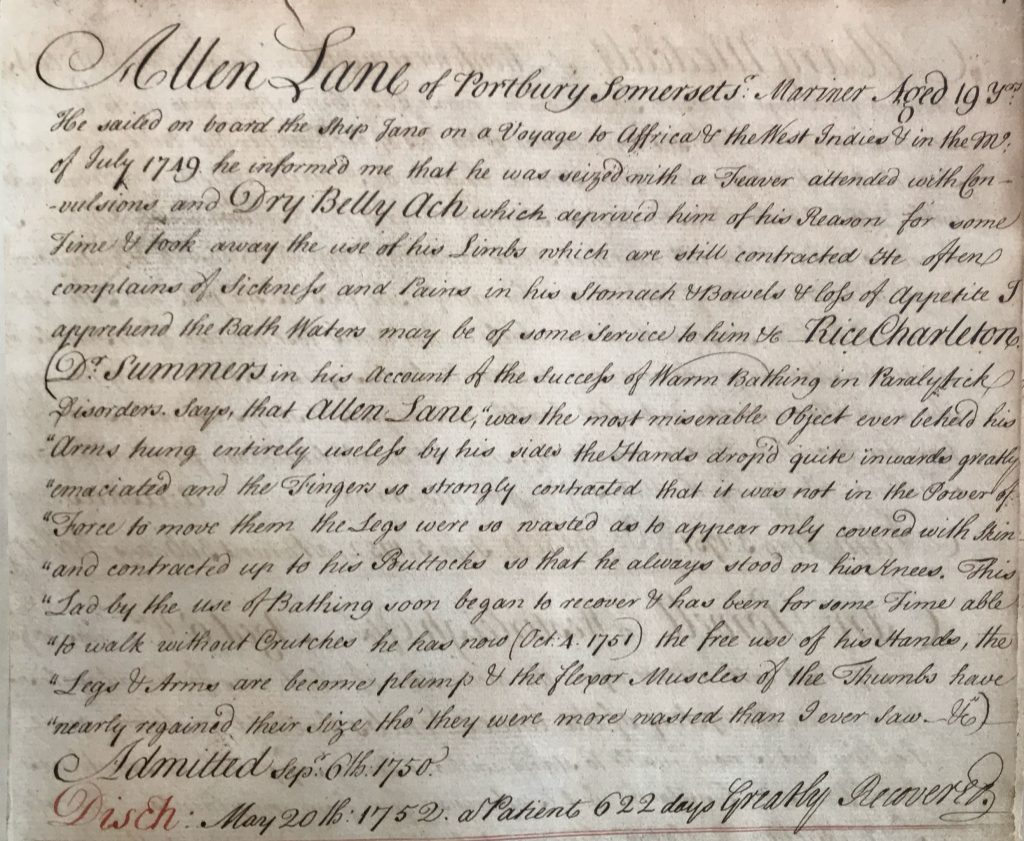

By the mid-18th century, doctors were realising that spa treatment was ineffective for many of the conditions on Turner’s list but bathing did appear efficacious for a small group of disorders which included certain types of paralysis, muscular and joint pains and some skin diseases. The picture by William Hoare which now hangs in the new therapy centre at the Royal United Hospital shows three patients with these conditions labelled palsy, rheumatism and leprosy. Add to this gout, which affected many of the more prosperous members of Georgian society, and rickets, a common condition in children, and you have the five conditions which, according to an analysis of contemporary records, seem to respond most favourably to spa treatment.

Lead poisoning was common in the past. Various sources were responsible including lead used in the manufacture of paint and glass, and contamination of cider and fortified drinks like port. Lead toxicity can produce a type of paralysis known as wrist drop. It can also cause kidney damage leading to gout if the person is eating a protein-rich diet. Muscular pains are also a feature. Some years ago, research was done into the effects of prolonged immersion with only the head out of the water. Besides inducing various physiological changes in the body, the study demonstrated that prolonged immersion caused a more rapid elimination of lead in people whose levels were raised because of their work in the lead shot industry. This could be an explanation of why a period of time spent in Bath having regular sessions of immersion in one of the city’s baths caused real improvement in conditions caused by lead toxicity.

The results of the study go much of the way to explain the success of the spa during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

All the city baths in the 17th and 18th centuries were outdoors. Sunlight may have played a part in improving skin conditions like eczema and psoriasis which would also benefit from the hydrating effect of immersing the skin and exposure to ultraviolet light. The latter would have also helped ameliorate rickets by stimulating Vitamin D production.

It is often said that improvement of a patient’s condition was psychosomatic and the treatment was only a placebo. Undoubtedly, this played some considerable part in the “cure” but it was evidently not the only reason for success of the spa in the 18th century. Even today, the buoyancy and warmth of the water is used to good effect for hydrotherapy, although the mineral content is not considered essential for treatment and the hospital hydrotherapy department in its new site is content to use heated tap water.

Article by Dr Roger Rolls