Bath’s historic association with warm spa water bathing enjoyed by visitors and relatively prosperous residents, is well recognised and extensively documented. However, the popularity of cold-water bathing, as practised by thousands of local people, most of whom were on relatively low incomes during the 19th and 20th centuries, is comparatively unacknowledged. Those bathers, who appear to us to be particularly hardy in the context of modern sensibilities, would not have been aware of the full array of health benefits derived from their exertions in cold water.

The Romans

More than a thousand years before the heyday of the Bath Spa, the Roman Baths in the same city were characterised by the range of facilities designed for successive warm water (the tepidarium) bathing and hot water (the caldarium) bathing, the latter deploying the hot springs rising in the centre of the basin shaped landscape. The final plunge would be into cold water (the frigidarium). The Romans acknowledged the benefits for their military veterans.

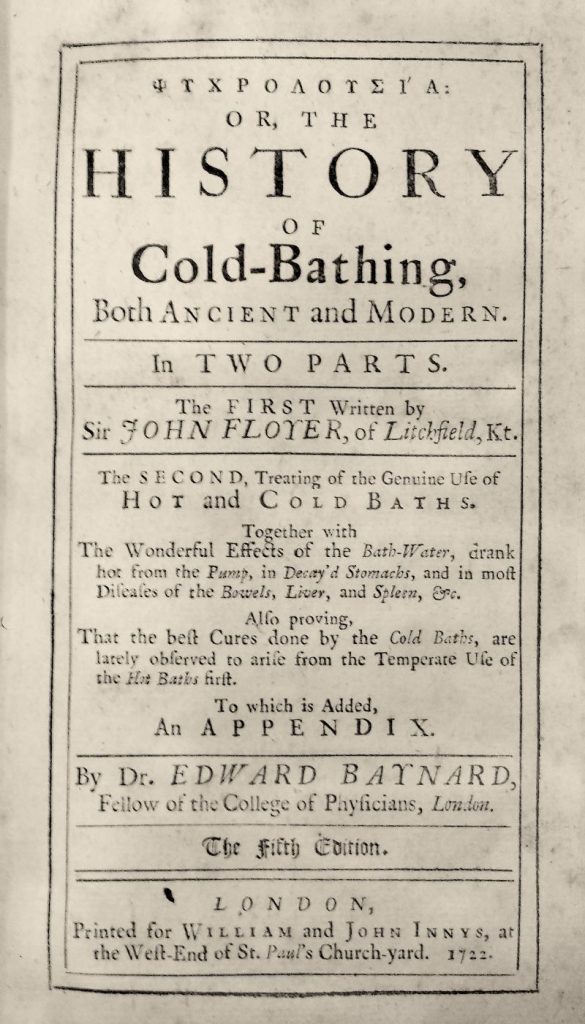

Sir John Floyer

Cold water bathers in rivers and ponds in the medieval and early modern period would have used limited strokes, such as those advocated by Sir John Floyer whose books on swimming practice, illustrated with frog-like movements in water, helped to popularise the therapeutic use of cold baths in the 17th century. He initiated the construction of baths in his hometown of Lichfield.

Wesley's Influence

It was a nationally known religious leader, very active in the Southwest of England, John Wesley, whose advocacy had caused cold water bathing to be more widely supported and practised. He considered that cold bathing prevented many diseases, helped the circulation of the blood; and prevented the danger of catching cold. Wesley’s view summarised in his book ‘Primitive Physick’, published in 1747 was that:

“Cold bathing is of great advantage to health; it prevents abundance of diseases. It promotes perspiration, helps the circulation of the blood; and prevents the danger of catching cold.”

These observations of Wesley’s were prescient in their acknowledgement of cold water’s benefits in relation to the body’s defences against infection.

Bath's Bathers

The social reputation of the hitherto nationally prominent Bath Spa was declining by 1800 though other spas in England still had a level of popularity. At the same time, medical opinion in England was tending to emphasise the benefits of sea bathing and cold-water bathing, rather than spa bathing in warm mineral waters. Physicians in the 18th century and at the turn of the 19th century considered that cold water bathing was particularly helpful for chronic medical conditions such as rheumatism and skin conditions.

Water treatments could range from leg or arm immersion to full body immersion. At the Bath Spa in the late 18th century, the warm water bathing could optionally be complemented by dousing in cold water – this practice was known as ‘bucketing’ and was thought to promote good health overall. Bucketing and prescribed full – body cold water plunging as a ‘shock’ was an aspect of the stringent treatment prescribed for relatively advanced mental health conditions.

In Bath, the renowned minister, Reverend William Jay who preached at the Argyle Chapel, was an active proponent of the health benefits of cold-water bathing.

The Cold Bath in Widcombe

A spring-fed cold bath which was opened by Thomas Greenaway in Claverton St, Widcombe, Bath at the beginning of the 18th century. Maurice Scott noted that ‘This bath was recommended to patients by Dr Oliver, a physician at the Mineral Water Hospital (later to become the Royal Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases). The Hospital recorded a desire that their patients could benefit from Mr Greenaway’s Cold Bath. The building was demolished in 1966 to make way for road developments.

River Bathing

In common with other towns and cities, river bathing in the Avon in Bath was a leisure activity for men of all classes during the 18th century, to the extent that a local act prohibiting nude bathing in the river Avon, the Bathwick Water Act, was passed in 1801. Concerns that led to this ban were not related to the water quality or the risk of drowning but rather focussed on public decency and respectability. Despite those moral objections, rivers, if not substantially polluted by industry during the Industrial Revolution, remained a venue for bathing for a cross‐section of social classes.

Nationally, river bathing had never diminished in popularity from the Middle Ages, as a form of recreation. As the wealthier segments of society changed their own bathing habits and more clearly associated it with health and cleanliness, they also developed more negative views about the hygiene of river bathing. In the early Victorian period, safety became an important consideration – there were regular newspaper stories of accidental drowning associated with bathing in rivers and lakes.

One alternative to bathing in the river in Bath in the early 19th century was mud bathing – local bathers, especially younger men with limited financial resources, resorted to the marl pits in the Bathwick area just off the river Avon. Marl pits are the sizable mud and water filled holes left behind after marl (a mix of earth and lime used to improve soil productivity) had been excavated. But mud bathing would have limited attractions and consequently, the idea of a more private, relatively clean, and attractive bathing facility would have taken shape.

The Pleasure Baths

The Bathwick Water Act was part of the context for the initiative to build the Pleasure Baths that became known as the Cleveland Pools. The building project was funded by subscriptions, paid by eighty-five professional men, or men having business interests in the city. The local press recorded the first swimming opportunities in 1817.So safe, private cold-water bathing became available on a fee-paying basis.

The Pleasure Baths (now known as the Cleveland Pools) were a convenient and comfortable adaptation of swimming in the river Avon: river water was diverted to flow through to the original main pool, with steps for access. A simple filter was designed to trap debris from the incoming river water, and it is possible that springs came up from the base of the pool (as they still did in the 20th century), thus mixing spring water with the river water flow.

The Ladies’ Pool at the Pleasure Baths was a secluded plunge pool for health –as a plunge pool from the very first days of the Pleasure Baths. The spring water supplying the Ladies Pool was channelled through cast iron piping and is likely to have originated in springs whose water was captured in a sizable cistern located in the Sydney Gardens.

The Water Cure

In the wider social context, hydropathic therapy or ‘the water cure’ was practised throughout Britain by the 1840s. The water cure could involve alternate hot and cold-water drenching or solely cold water. It was advocated for a wide range of medical conditions including mental illness. This treatment was delivered through shower arrangements, or patients were immersed in individual baths and covered in sheets. Great Malvern became the national focus for the development of the water cure. Near Bath, the West of England Hydropathic Establishment at Limpley Stoke offered the full range of cold water treatments.

Public health concerns took on a higher profile in the mid – 19th century. The early decades of the 19th century had seen successive cholera epidemics in the cramped poorer areas by the Avon, known as the Dolemeads. From the mid-century, it became established knowledge that the disease was caused by contaminated water. The links between hygiene and health, especially preventable disease, were more recognised and actively promoted. Bath’s city government, unlike the large metropolitan cities, was relatively slow to consider the creation of public bathing facilities that could be used for personal hygiene, but an outcry did develop concerning the need for low cost, or free, clean swimming facilities.

Thousands of city residents resorted to swimming at a free bathing facility at the Darlington Wharf, on the Kennet and Avon Canal. This popular, free bathing place was clearly unhygienic, being stagnant and polluted by the many barges that plied the Canal, with their cargoes of coal from the Somerset coalfields and other goods. Yet it was used by huge numbers of local bathers.

Consideration of a municipal pool for Bath residents was not resolved until the 1890s when demand for cold water swimming was even more substantial, associated with more widespread public interest in swimming as a competitive sport.

By 1900 the Bath Corporation had purchased the Cleveland Baths and opened them for widespread free or low-cost public use. Eventually, in the early 1900s, cold mains water was introduced. The Cleveland Baths then experienced peaks of popularity with thousands of people swimming in the high seasons during most of the 20th century up till their closure in the mid – 1980s.

Modern Cold Water-Based Treatments

Modern treatments incorporating cold – or ice – water include the relief of muscle fatigue. Indications are that colder water temperatures may help substantially to relieve inflamed muscles, muscle spasms and oedema. But more widely, in relation to the benefits of cold-water swimming, relevant studies summarised in the New Scientist pointed to the possibility of increased immunity. Several studies have reported a link between cold water swimming and fewer respiratory infections in addition to the improvement of mood disorders and a general sense of well-being. So, providing that the risk of cold-water shock is avoided by gradual immersion, the evidence of the health benefits of cold-water bathing is increasing, bearing out the historical observations and prescription of many respected medical practitioners.

Article by Dr Linda Watts

References

Bath General Hospital Minute book, Vol 1, October 1742.

Floyer J. (1732) Psychrolousia or the history of cold-water bathing. Innys and Manby, London.

George A. (2021) Cold water swimming: what are the real risks and health benefits? New Scientist, 10 March 2021.

Scott M. (1993). Discovering Widcombe and Lyncombe, Bath. Widcombe Association, Bath.

Wesley’ J. (1737). Primitive Physick. William Pine, Bristol.